November 4, 2025 · Zifeng Wang, PhD, Keiji AI

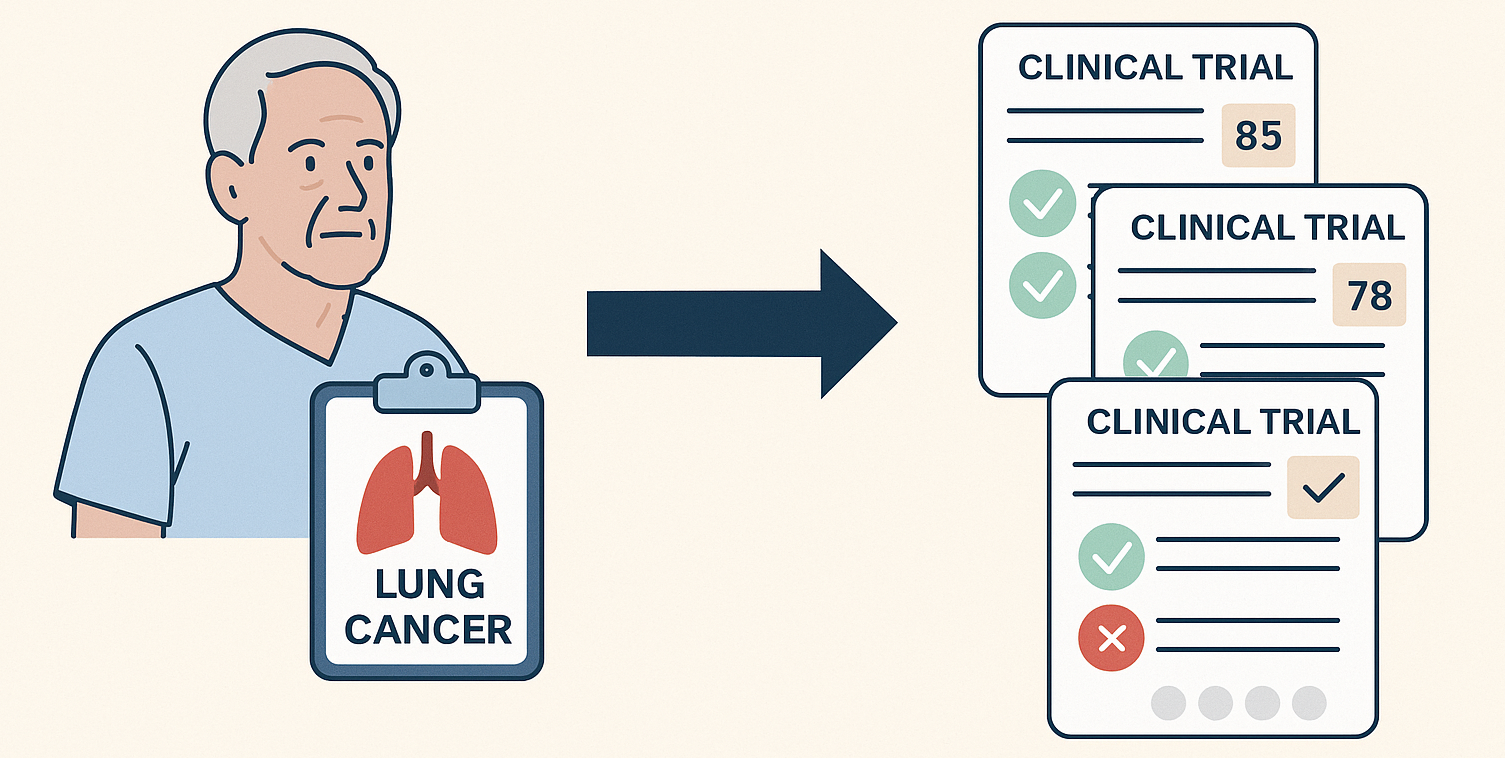

Patient recruitment is the headache no one talks about at parties. Trials stall. Budgets burn. Great ideas never meet the right people. That is why many teams are turning to generative AI to help. In the research world, folks split the problem into two directions. Trial to patient means a trial is hunting for candidates tucked inside hospital records and registries. Patient to trial is the flip side. A clinician or a motivated patient asks which trials might fit and wants a trustworthy short list. Same mission, different starting point.

This post digs into patient to trial. Think about the inputs you see in the real world. Sometimes it is a simple question like find me an active lung cancer trial nearby. Other times it is a stack of clinic notes, pathology reports, lab panels, and a medication list that is three lines long. The job is the same. Read the record. Search the universe of trials. Decide who fits which criteria and rank the options so a human can make a call with confidence.

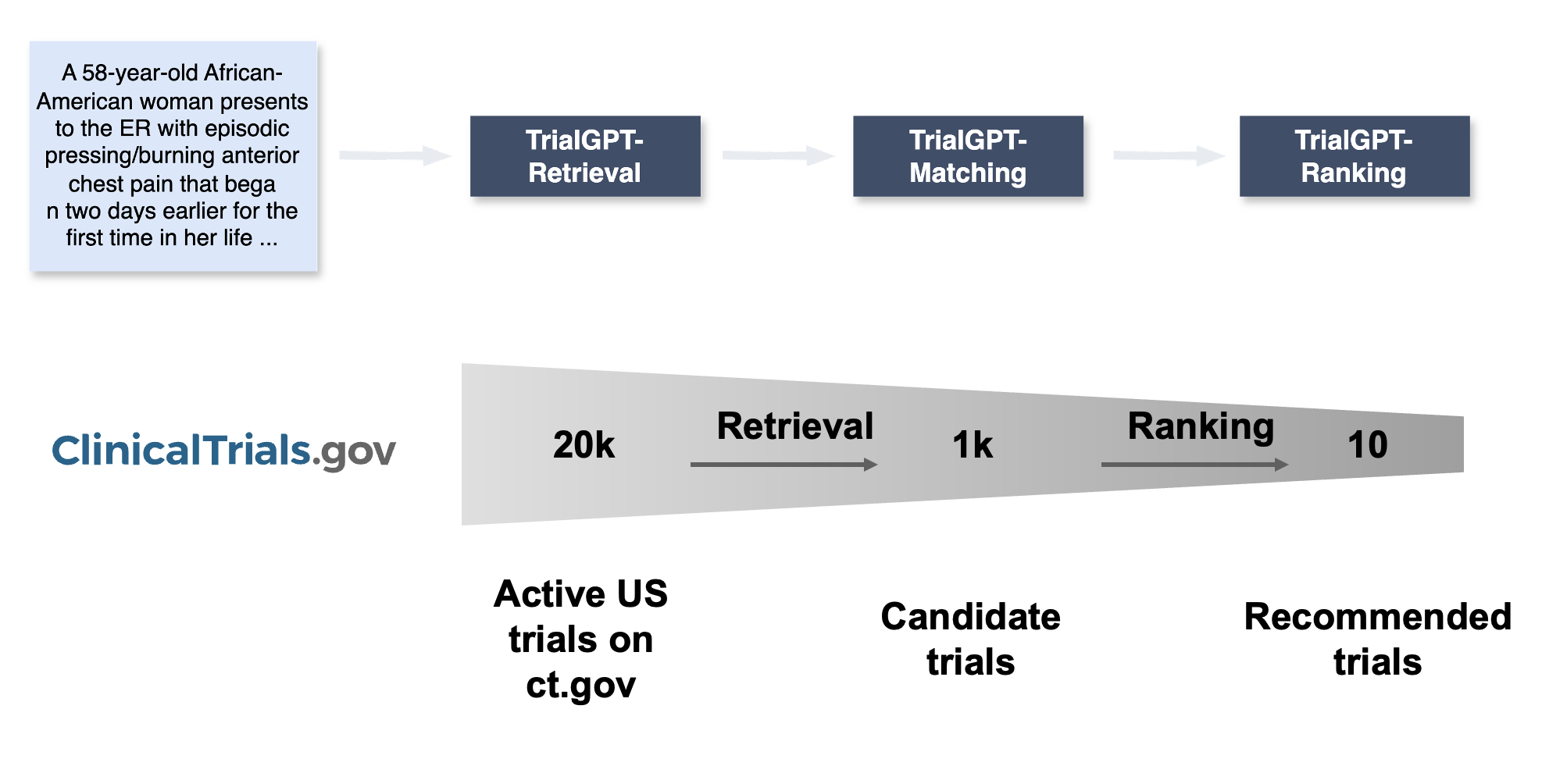

The TrialGPT Pipeline

That is the core idea behind our research project TrialGPT [1]. The pipeline is simple to describe and hard to execute well. Step one. Parse the patient record. Step two. Query and retrieve promising trials. Step three. Check eligibility criterion by criterion and produce a ranked list. Generative models give us a shot at doing this without the giant labeled datasets that usually power machine learning. In computer science speak, they are pretty good at zero shot learning. In human speak, you can describe the task in plain language, give a few examples, and the model gets to work.

How It Works in Practice

Here is what that looks like in practice. You hand the model a patient note. You ask it to surface the nuggets that matter for matching. Age. Sex. Diagnosis and histology. Stage. Biomarkers. Lines of therapy. ECOG. Key comorbidities. Concurrent medications that might collide with an exclusion rule. It writes these down in a tidy, structured summary. Now you can talk to a trial database in its own native language. We built a tool wrapper around the public clinical trials registry so the model can compose clean search requests. The model generates search keywords that a human might forget on a busy day and plugs them into a hybrid retrieval system that mixes exact matches and semantic similarity. That gives you a shortlist of active trials, not a firehose.

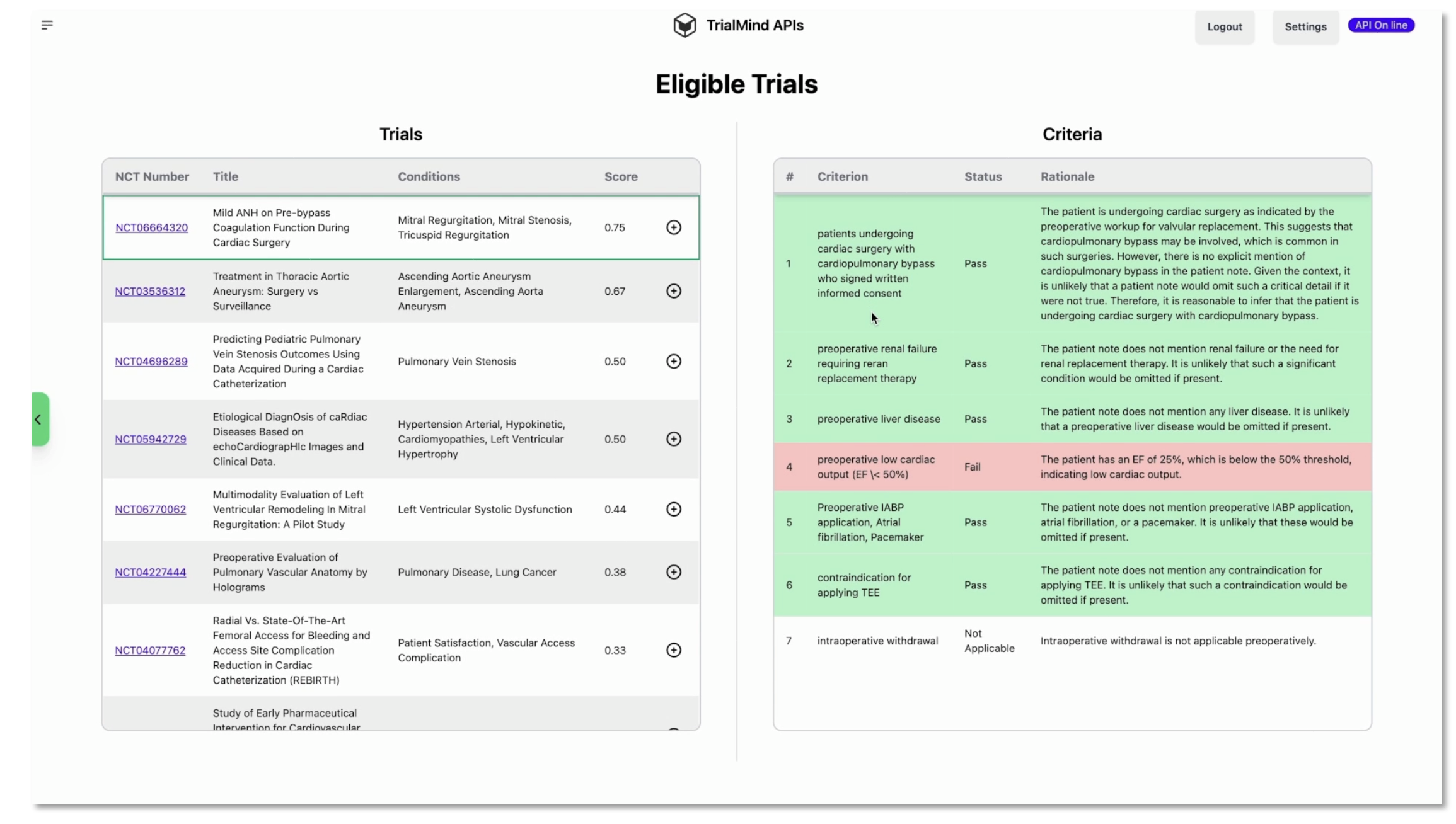

Next comes the part clinicians care most about. For each candidate trial, the model walks through the inclusion and exclusion criteria one by one. It explains the reasoning in plain language. It points to the exact sentences in the patient note that support that decision. It labels the outcome for each criterion. Included. Not included. Not enough information. Not applicable. Then it aggregates those findings into a per trial score so you can sort the list and quickly spot deal breakers.

Trust, Speed, and What's Next

If you have ever tried to automate this, you know the hard questions show up fast. How do you know the model is making good calls. First, you measure. We worked with collaborators to build a set of patient note to criterion annotations and tested the system against those labels. We also asked medical experts to review explanations and evidence spans so we were not only checking the answer but also where the answer came from. Second, you show your work in the interface. A ranked list is helpful. A ranked list that also shows criterion level decisions and the lines from the note that drove them is something a clinician can trust and override if needed.

A big benefit of this approach is speed. Recruiters and research nurses spend a lot of time scanning criteria just to say no for a clear reason. When the system calls out which exclusion points are triggered and highlights the evidence, screening becomes a quick decision instead of a deep dive. And when the system is unsure and flags not enough information, that prompts a targeted chart check rather than a hunt through every prior visit.

Let's bring it back to the human in the loop. No one wants a black box telling a patient yes or no. TrialGPT is built to assist, not replace. It narrows the field, surfaces reasons, and organizes evidence. A recruiter remains the decision maker. In our experience, this combination saves time on screening and increases consistency across team members. That time gets reinvested in calling the right patients and closing the loop with referring clinicians.

Where does this go next. Two directions. On the patient to trial side, the playbook is to keep expanding the inputs the model can handle and to plug into more trial registries beyond a single database so coverage improves. On the trial to patient side, which we will talk about in the next post, the problem flips. You start from a trial and translate its criteria into queries that find eligible patients across electronic health records while respecting privacy and governance. The tools are similar. The orchestration is different. Together, the two directions can make recruitment proactive rather than reactive.

References

[1] Jin, Q., Wang, Z., Floudas, C. S., Chen, F., Gong, C., Brackett, A., ... & Lu, Z. (2024). Matching patients to clinical trials with large language models. Nature Communications, 15, 9074. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53081-z