March 12, 2025 · Jimeng Sun, PhD, CEO of Keiji AI

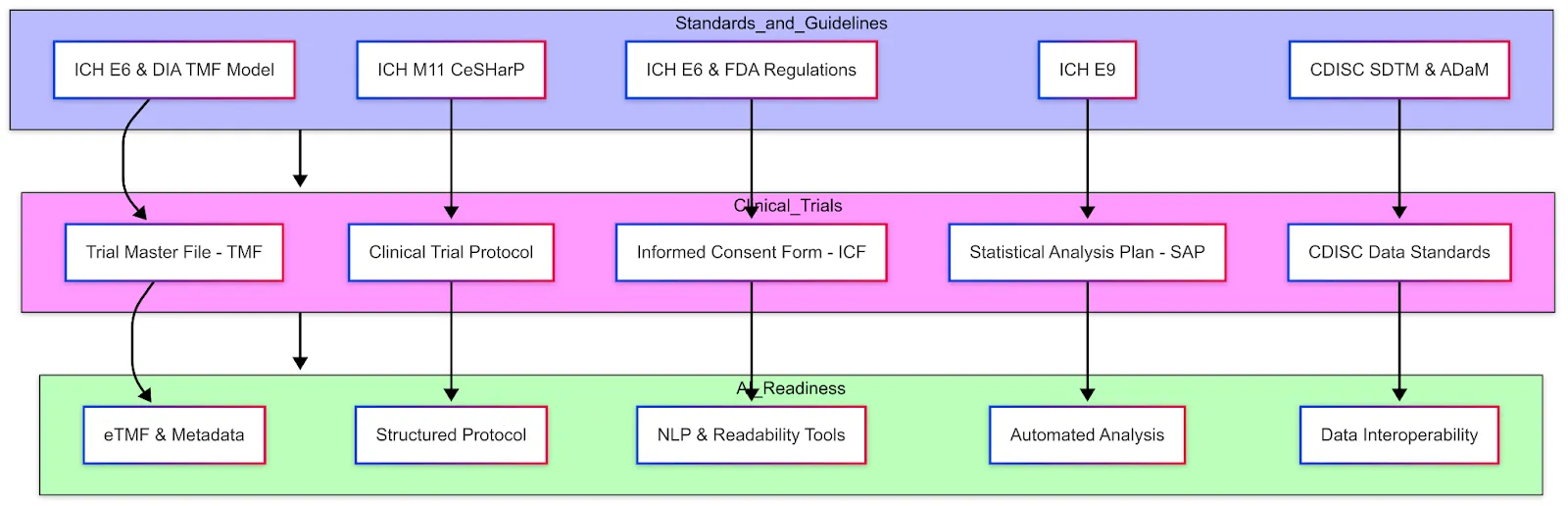

Clinical trials produce and rely on a variety of data and documents, all of which must adhere to certain standards to ensure integrity, interoperability, and compliance. Key data elements and standards include:

Trial Master File (TMF) and Essential Documents

The TMF comprises all the essential documents that allow evaluation of the trial's conduct and the quality of the data. Per ICH GCP (E6 R2), essential documents include items such as the study protocol and amendments, investigator brochures, signed informed consent forms, ethics committee approvals, regulatory authority approvals, delegation logs, monitoring visit reports, audit certificates, clinical study reports, etc. Essentially, it's the paper (or electronic) trail of the entire study. These documents are typically grouped by stage (before study, during study, after completion) according to ICH E6 Section 8. Regulators may inspect the TMF to verify that the trial was conducted properly and that all necessary approvals and procedures are documented. Standards like the DIA TMF Reference Model provide a standardized structure and nomenclature for TMF contents, which many sponsors follow to organize their eTMF.

The DIA TMF Reference Model (now part of CDISC) provides a standardized framework for managing documentation in clinical trials. It defines a structured taxonomy and metadata system, organizing essential trial documentation into clearly delineated Zones, Sections, and Artifacts, thus streamlining regulatory compliance and audit readiness. Each artifact represents a specific document type, classified as either core (required if applicable) or recommended. The model is designed to reduce complexity, standardize terminology across diverse stakeholders—including trial sponsors, CROs, and regulatory agencies—and facilitate interoperability across electronic Trial Master File (eTMF) systems.

AI-Readiness: For AI researchers working in clinical trials, this model helps ensure consistent documentation, promotes efficient data management, and supports regulatory adherence when developing automated systems or analyzing clinical trial data. Historically, TMF documents are unstructured (scans, PDFs). Converting them into an electronic structured format (via eTMF) with metadata tagging already improves accessibility. Efforts are underway to further standardize templates for some of these documents, which could enable AI to more easily search and extract information across trials. For instance, if all monitoring reports followed a structured template, an NLP algorithm could quickly summarize common findings or compare protocol deviations across sites.

Clinical Trial Protocol

The protocol is the blueprint of the trial — a detailed document describing the study's objectives, design, methodology, statistical considerations, and organization. It outlines what will be done in the trial, how it will be conducted, and why each aspect is necessary. Typical sections of a protocol include background and rationale, trial design (e.g. randomized, placebo-controlled), subject inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment regimens, endpoints, study procedures and schedule of assessments, statistical analysis plan overview, safety monitoring plan, etc.

Because protocols can be very lengthy and vary in format between sponsors, a new standard is being developed: ICH M11: Clinical electronic Structured Harmonised Protocol (CeSHarP). The ICH M11 guideline (currently in draft) proposes a standardized protocol template with defined structure and content for each section, along with machine-readable technical specifications. The goal is that every trial protocol will follow the same organizational framework, making it easier for investigators, ethics committees, and regulators to navigate, and also enabling digital tools to parse protocol elements. For example, CeSHarP defines standardized section headers and even certain data fields within the protocol (like trial phase, population, etc.), which could eventually allow an AI system to automatically pull key parameters from the protocol.

AI-Readiness: A structured protocol is highly "AI-friendly" — it could allow an AI assistant to answer questions like "What's the primary endpoint of this study?" or "List the eligibility criteria related to cardiac health" instantly, instead of someone manually reading dozens of pages. This harmonized format (with defined XML/JSON tags for each section) is expected to greatly facilitate trial registry submissions and cross-trial metadata analysis once adopted. Until M11 is implemented, protocols remain narrative documents; still, sponsors often use internal templates and tools (some use AI-based writing assistants) to ensure consistency and compliance with ICH E6.

Informed Consent Form (ICF)

The ICF is the document through which trial participants are informed about the study and voluntarily agree to participate by signing. It explains in layperson terms the purpose of the study, procedures, risks, potential benefits, confidentiality of data, and the participant's rights (including the right to withdraw at any time). ICH GCP defines informed consent as an ongoing process, documented by a written, signed, and dated informed consent form. Every participant (or their legal representative) must sign an ICF before any study procedures occur, as mandated by ethics regulations.

Key standards/guidelines here include ICH E6 (which describes what should be in the consent form and the process around it) and local regulations (for example, FDA 21 CFR 50 in the US). Increasingly, electronic consent (e-Consent) is being adopted, where the ICF is delivered via a tablet or web portal, often with interactive elements (videos, quizzes to confirm understanding) and electronic signature capture. eConsent systems must meet regulatory requirements for electronic records and signatures.

AI-Readiness: The language in ICFs is an area of active improvement — some groups use AI readability tools to ensure the text is understandable to people with varying health literacy. While ICFs are mostly document-based, there is interest in using NLP to compare an ICF against the protocol (to ensure the ICF adequately covers all procedures/risks listed in the protocol). Additionally, large collections of ICFs could be mined by AI to identify common information that participants want or to detect overly complex language. However, since ICFs often require customization for each study and site (different languages, institutional requirements), standardization is challenging beyond general guidelines.

Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP)

The SAP is a document that details the statistical methods that will be used to analyze the trial data. While a high-level analysis plan is typically outlined in the protocol, the SAP provides a much more granular roadmap for the statisticians. It prespecifies how each endpoint will be analyzed, how missing data will be handled, definitions of analysis populations (e.g. intent-to-treat vs per-protocol), details on any interim analysis, and the format of tables and figures to be generated. The SAP is usually finalized before trial unblinding or database lock to avoid bias in analysis decisions.

In fact, ICH E9 (Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials) encourages a clear distinction between trial design and trial analysis and suggests that the protocol and a separate SAP should pre-specify the analyses to uphold the integrity of results. According to regulatory guidelines, the SAP should be sufficiently detailed that an independent statistician could replicate the planned analyses.

Standards: ICH E9 is the primary guidance covering statistical principles — including concepts like intent-to-treat (ITT) population, multiplicity adjustments (for multiple endpoints), and interim analysis considerations. An important recent update is ICH E9 (R1) Addendum on Estimands and Sensitivity Analyses, which introduces the "estimand framework" to align trial objectives, endpoints, and handling of intercurrent events (like treatment discontinuation or use of rescue medication). This has implications for how SAPs are written — now statisticians explicitly define the estimand (target treatment effect) and ensure the analysis methods (estimator) match that estimand, with sensitivity analyses for robustness. The SAP must reflect these choices.

AI-Readiness: Much of the SAP is structured text and statistical code. Sponsors often use template wording for common methods, but each trial's SAP is unique. An area where AI could assist is in auto-generating draft SAPs based on protocol information (for instance, an AI tool could propose statistical methods suitable for the endpoints defined). Also, since analysis datasets follow standards (see below), parts of the SAP (like variable definitions, dataset structure) are standardized. There are emerging tools that can take an SAP and programmatically execute it (conversion into statistical programming code), and one can envision future AI that validates if a SAP adheres to regulatory guidelines (e.g., checks that all primary endpoints have an analysis method stated, etc.). But for now, SAPs are written by biostatisticians following guidelines like ICH E9 and FDA's Biostatistical Guidance.

CDISC Data Standards (SDTM, ADaM, etc.)

The Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) provides standardized formats for clinical trial data that are now widely required for regulatory submissions. The two main CDISC standards used in trials are SDTM (Study Data Tabulation Model) and ADaM (Analysis Data Model).

SDTM defines a standard structure for clinical trial tabulation data — essentially the collected data for each subject. It organizes data into domains (such as DM = Demographics, AE = Adverse Events, LB = Lab Results, VS = Vital Signs, etc.) with consistent variable names and formats.

ADaM defines standards for analysis datasets that are derived from SDTM, structured in a way that supports the specific statistical analyses (e.g., an ADaM dataset for efficacy might have one record per subject per time point with derived variables like change from baseline).

Along with these, DEFINE-XML is an XML metadata file that accompanies the datasets to describe their contents, and Controlled Terminology standards ensure consistent coding of terms (e.g., using MedDRA for adverse event terms, WHO Drug Dictionary for medications).

Regulatory agencies have embraced these standards: since December 2016, the FDA (and Japan's PMDA) mandate that NDAs/BLAs must submit trial data in FDA-supported CDISC formats. This means sponsors need to convert their study datasets to SDTM for submission and provide ADaM datasets for key analyses, along with metadata and the Reviewer's Guide.

Data Interoperability: CDISC standards greatly enhance interoperability because any analyst familiar with SDTM can navigate any trial's data once converted. It allows regulators to use standardized tools — the FDA has a repository of scripts and programs that can automatically run on SDTM/ADaM to generate review outputs. This consistency is also crucial for AI applications: if thousands of past trial datasets are in SDTM, an AI system can be trained across them to find patterns (whereas if every trial had its own schema, that would be far more difficult). In practice, within a company, internal data may first be captured in the EDC's format (often based on CDASH — Clinical Data Acquisition Standards Harmonization, which is a CDISC standard for CRF design corresponding to SDTM). Then data is mapped to SDTM for submission.

AI-Readiness: Having data in SDTM/ADaM opens the door for AI to analyze cross-trial data. For example, an AI could be fed many oncology trial datasets to learn predictors of response, since the tumor measurement data and response criteria would be structured in a consistent way (e.g., in the RS domain for response assessments). Additionally, data quality tools can use the standards to detect outliers or anomalies (for instance, flag if a male patient has an SDTM DM domain entry indicating pregnancy). In summary, CDISC standards are foundational for data interoperability and essentially make clinical trial data "speak the same language," which is a prerequisite for effective AI analysis across studies.

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)

The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) is a clinically validated international medical terminology developed by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). It is utilized by regulatory authorities and the biopharmaceutical industry throughout the regulatory process, from pre-marketing (clinical research phases 0 to 3) to post-marketing activities (pharmacovigilance or clinical research phase 4), for the registration, documentation, and safety monitoring of medical products.

MedDRA's hierarchical structure consists of five levels:

- System Organ Class (SOC) — 27 classes

- High-Level Group Term (HLGT) — 337 terms

- High-Level Term (HLT) — 1,737 terms

- Preferred Term (PT) — 25,592 terms

- Lowest Level Term (LLT) — 85,668 terms

This structure facilitates the precise coding and analysis of clinical data, particularly adverse events.

Example 1:

- SOC: Gastrointestinal disorders

- HLGT: Gastrointestinal signs and symptoms

- HLT: Nausea and vomiting symptoms

- PT: Nausea

- LLT: Feeling queasy

Example 2:

- SOC: Cardiac disorders

- HLGT: Cardiac arrhythmias

- HLT: Supraventricular arrhythmias

- PT: Atrial fibrillation

- LLT: AFib

Incorporating MedDRA into clinical trial data standards enhances data consistency and interoperability. Its standardized terminology allows for accurate communication and analysis of safety information across different stages of drug development and post-marketing surveillance. Additionally, MedDRA's role in regulatory submissions is critical, as it is often mandated by health authorities for adverse event reporting.

AI-Readiness: For AI researchers, the structured nature of MedDRA offers opportunities for developing algorithms that can automatically code and analyze medical data. Recent advancements, such as the ALIGN system, demonstrate the potential of large language models to automate the coding of medical terms into MedDRA codes, thereby improving the efficiency and accuracy of data harmonization in clinical trials. In summary, MedDRA is a pivotal component of clinical trial data standards, ensuring the uniformity and quality of medical terminology used in regulatory activities. Its integration into data management practices is essential for maintaining data integrity and facilitating effective communication among stakeholders in the clinical research community.

Regulatory Guidelines (ICH E6, E9, E11, etc.)

These guidelines ensure trials are conducted and analyzed to high ethical and scientific standards, and they also indirectly influence data collection and management practices:

ICH E6 (R2) — Good Clinical Practice (GCP): This is an international GCP guideline that covers all aspects of trial conduct — from study design, investigator responsibilities, sponsor responsibilities, to essential documents and record-keeping. It doesn't dictate data formats but sets expectations for quality and documentation. For example, E6 requires that all trial information be recorded, handled, and stored in a way that allows accurate reporting, interpretation and verification, which underpins the need for things like audit trails and source data verification. E6(R2) also introduced the concept of risk-based quality management, encouraging sponsors to focus on critical data and processes — this ties in with data standards and AI in that sponsors are now leveraging analytics to identify "critical data" to monitor more closely. A coming update E6(R3) will further emphasize flexibility and modern methods (like centralized monitoring and use of tech).

ICH E9 — Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials: As discussed, E9 (1998) lays out principles for design and analysis (randomization, blinding, handling deviations, ITT principle, etc.), and the E9(R1) addendum (2020) on Estimands ensures clarity in describing the treatment effect of interest. Adhering to E9 means in the data context that trials should plan analyses in advance (hence SAPs) and that data collected should support those analyses (for example, collecting reasons for treatment discontinuation so that different strategies for handling those can be applied in analysis per the estimand). E9 also underscores the need for data quality in terms of minimizing bias and variability — which translates into careful trial conduct and data cleaning procedures. For AI, a noteworthy point is that AI algorithms used in trial analysis must align with these principles — e.g., an AI model that predicts an outcome would need to be consistent with pre-specified analysis and validated, otherwise it might conflict with the statistical rigor expected by E9.

ICH E11 — Clinical Trials in Pediatric Population: This guideline addresses the special considerations for including pediatric subjects. It emphasizes ethical considerations (assent of the child in addition to parental consent, minimizing unnecessary trials in children), proper formulation adjustments, and safety monitoring for kids. Data-wise, it might mean collecting additional long-term safety data (since effects on growth and development are crucial) and using appropriate pediatric efficacy endpoints. One concept is pediatric extrapolation — using data from adults or other populations to reduce the amount of data needed in children, which was expanded in E11(A) addendum. Interoperability is less an issue here, but standardization and careful planning are — age categories are defined (e.g., neonates, infants, children, adolescents) and trials should ensure data is captured to allow analysis by age group. AI note: There is interest in using AI modeling to predict pediatric dosing or outcomes from adult data (model-informed drug development). While not a part of E11 per se, such approaches align with the goal of pediatric trials: to gain necessary data with as few children as possible exposed. If AI can help simulate or extrapolate some information, that could reduce pediatric sample sizes ethically.

ICH M11 — Clinical Electronic Structured Harmonised Protocol: As mentioned earlier, M11 is a multidisciplinary guideline aiming to harmonize the protocol format. Once in effect, it will standardize how trial protocols are written globally. This will greatly improve data exchange — for instance, study registry databases could automatically ingest protocol details rather than relying on manual entry. It also enhances transparency: regulators and sponsors could more easily compare protocols, and patients could more easily find key info. Additionally, M11 includes a plan for an electronic exchange standard for protocols, which is an XML representation. This is very "AI-ready" because an AI could parse protocol elements without NLP if they're provided in a structured form. While M11 is still in draft, companies are anticipating it by structuring more of their protocol content (some already use structured authoring tools where each eligibility criterion or endpoint is an object that can be reused and compared across protocols).

Data Interoperability and AI-Readiness

In general, the industry is moving towards greater data interoperability — making sure that data from different sources (EDC, labs, patient devices, RWD, etc.) can be integrated. Standards like HL7 FHIR (for EHR data exchange) are starting to intersect with clinical research. For example, there are initiatives to auto-populate EDC forms from EHRs using FHIR, which would drastically reduce transcription errors and workload.

For AI, having interoperable data is key: algorithms often need large, aggregated datasets to learn from. If each trial's data is siloed or formatted differently, it's hard to apply AI across them. That's why CDISC standards, controlled terminology, and structured protocols are foundational — they ensure that one trial's "blood pressure" data is in the same format and context as another's.

Furthermore, regulatory agencies are adapting their frameworks to accommodate AI and complex analytics. The FDA has proposed guidelines for using RWE in approvals, which implicitly covers AI-derived insights from large datasets. They are also grappling with how to validate AI tools used in trial conduct (for instance, if an AI is used to evaluate medical images as an efficacy endpoint measure, it might be considered an AI-based diagnostic that needs clearance).

In conclusion, clinical trial data standards (CDISC) and guidelines (ICH GCP, etc.) provide a framework that ensures data reliability and participant protection. They are the scaffolding upon which any AI or advanced analytics must build. As the field adopts structured protocols (ICH M11) and greater data sharing, we expect trials to become even more "machine-readable." This not only helps AI, but also humans — improving transparency, efficiency in trial set-up, and the ability to aggregate knowledge across trials. The end game is a state where a lot of trial data flows automatically from electronic health systems, gets analyzed with minimal manual intervention, and can be mined by AI to inform the design of the next generation of trials and therapies.