November 18, 2025 · Zifeng Wang, PhD, Keiji AI

If you ask most people what LLMs are good at in science, they will probably say something like: searching and summarizing papers. Type in a question, get a neat list of references and a tidy paragraph on top. Feels like a literature review, right? Not quite. Especially not in medicine. In clinical research, an actual systematic review of clinical trials is more like running a regulated manufacturing line than skimming papers on a Sunday afternoon. You have to follow PRISMA, which tells you exactly how to define your question, construct search strategies, track every inclusion and exclusion decision, and report everything in a way another group could reproduce and verify.

Oh, and in the end you are not just telling a story. You usually need a meta-analysis that quantifies effect sizes and uncertainty. This is what feeds into clinical guidelines, reimbursement decisions, and ultimately bedside care. So if you drop your question into something like OpenAI's Deep Research and hope it will give you a compliant systematic review, you will be disappointed. You might get useful exploration. You will not get something a clinical journal or guideline panel would accept as an SLR. That is the gap we started to work on.

TrialMind-SLR: Turning PRISMA into a Workflow, Not a Vibe

Our first step on this road is TrialMind-SLR, published in npj Digital Medicine [1]. The idea was simple to state and non-trivial to implement: take the PRISMA-style systematic review pipeline and turn it into a set of well-defined, controllable steps that LLMs can help with, without breaking reproducibility.

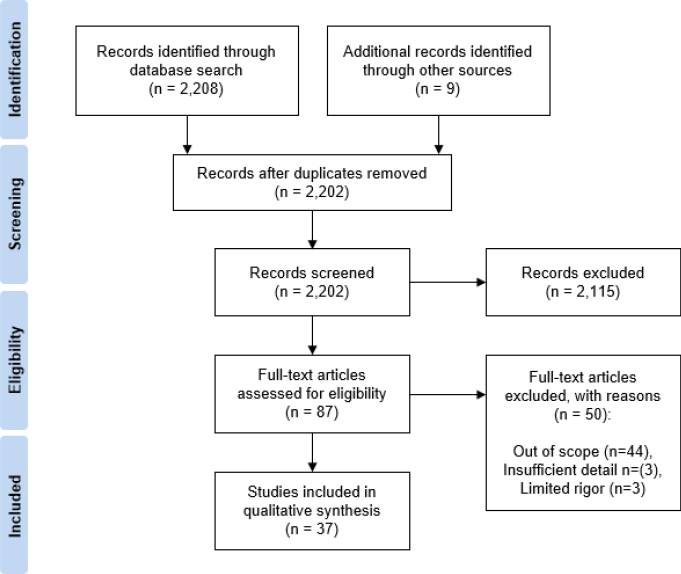

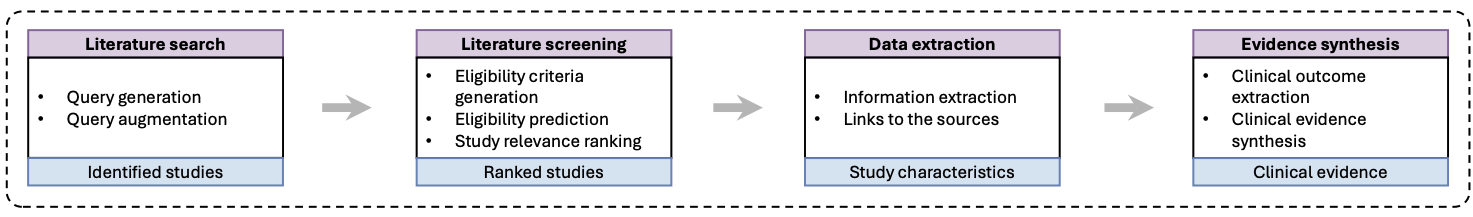

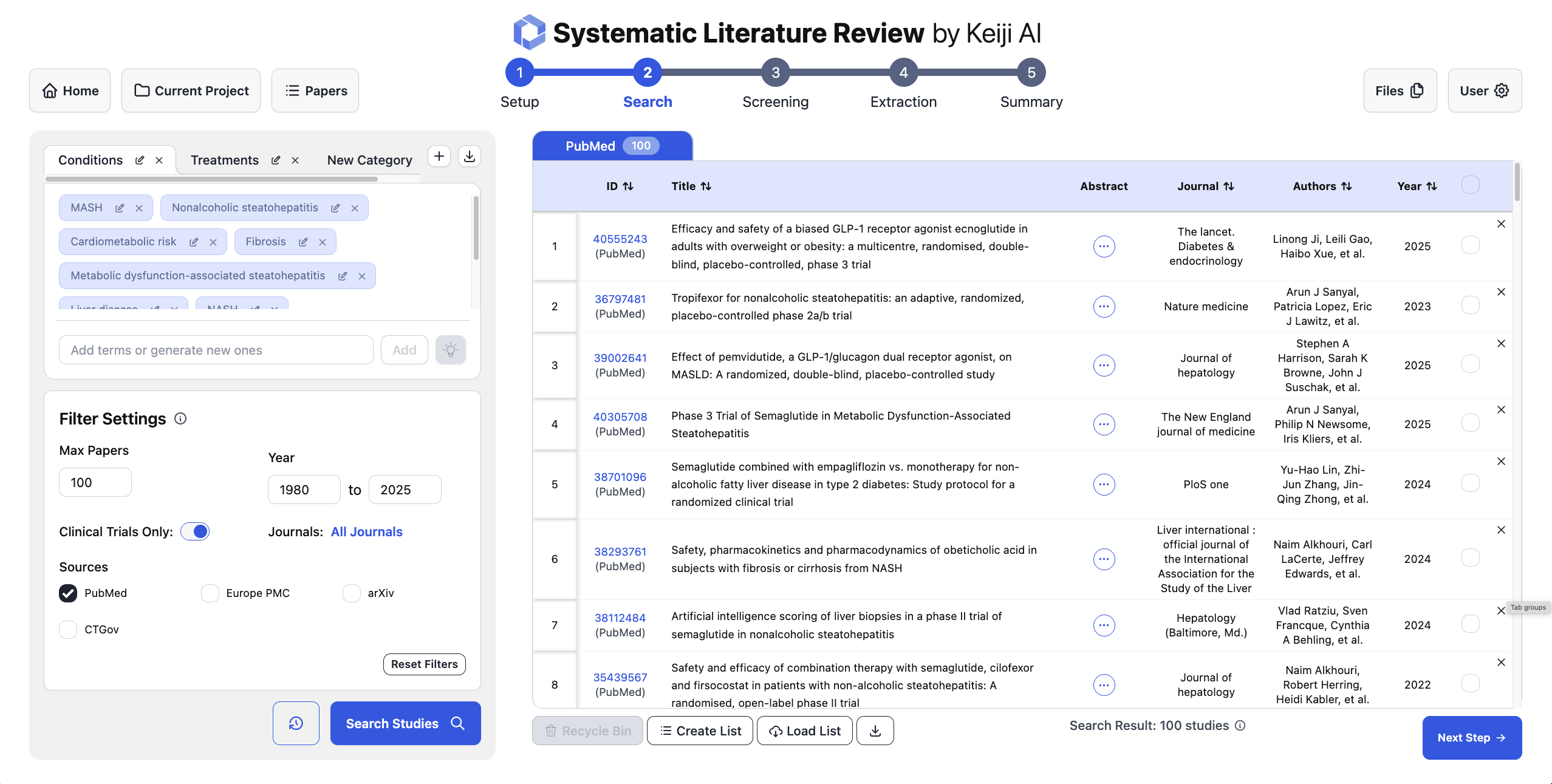

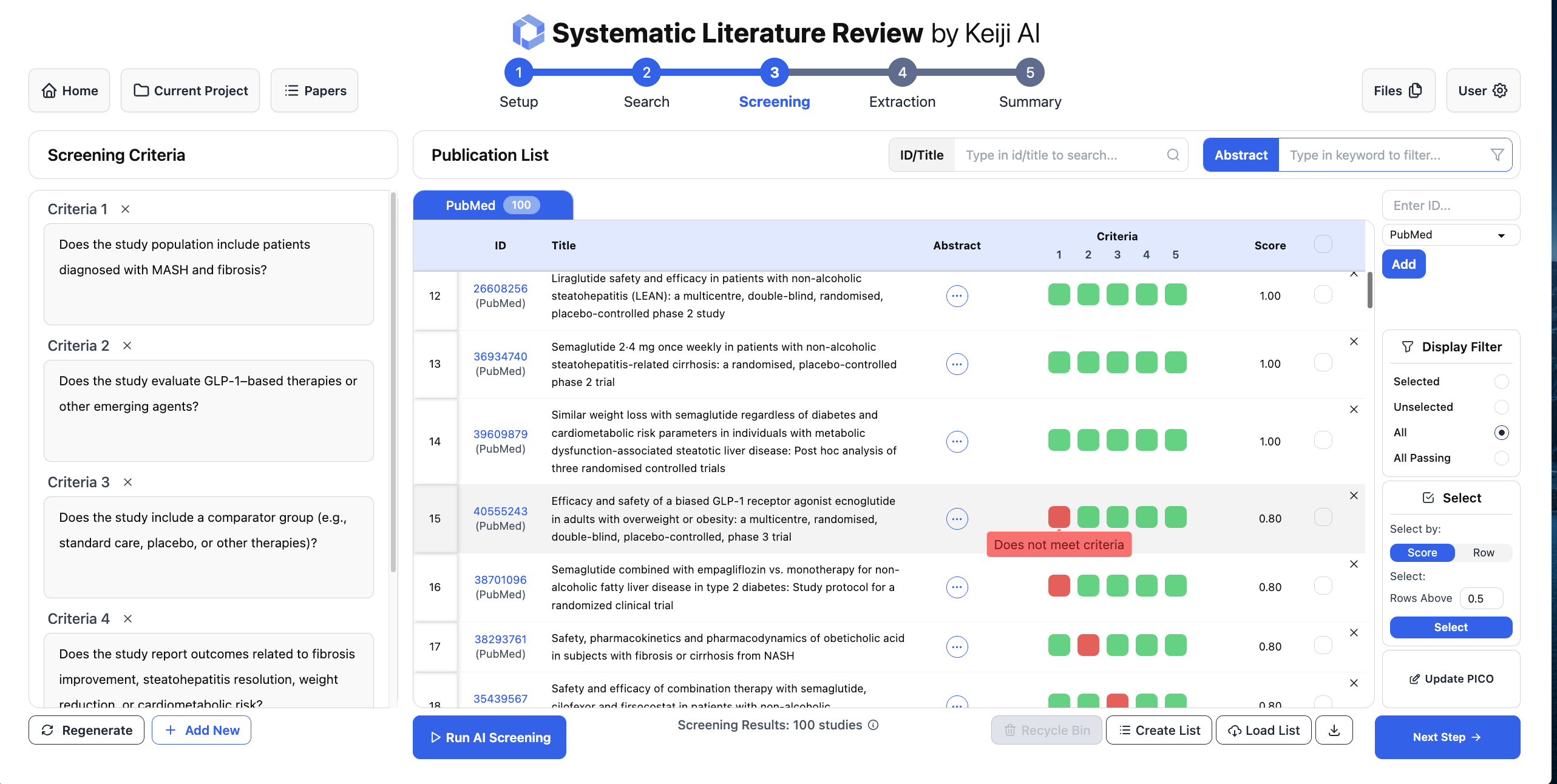

Conceptually, we split the workflow into four stages that mirror how clinical SLRs are actually done: (1) Literature search, (2) Study screening, (3) Data extraction, and (4) Evidence extraction and synthesis.

The input to this whole pipeline is a clearly defined review question using the PICO framework: Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. For literature search, the input is PICO and the output is not a final answer, but a search strategy. That means specific condition terms, intervention names, and outcome phrases that can be turned into reproducible queries for PubMed and trial registries. The objective here is twofold: maximize recall so we do not miss important trials, and make sure the exact query terms can be reported in the Methods section of the review. So the LLM is not "finding the answer on the internet." It is doing query design under constraints.

For screening, we take the review's eligibility criteria, encode them in a structured way, and use the LLM to label candidate studies as include or exclude. Because each decision is based on explicit criteria and the inputs are logged, you can audit and rerun this step later. Instead of months of human screening, you can get machine-assisted triage over thousands of trials in minutes, with consistent logic and a clear paper trail.

The important pattern is that each module has a precise input and output, aligned with how PRISMA and clinical SLRs actually work. Stitch them together and you get a pipeline that feels like a conventional review, except with LLMs quietly doing a lot of the repetitive heavy lifting behind the scenes.

LEADS: When You Realize Generic LLMs Are Not Quite Good Enough

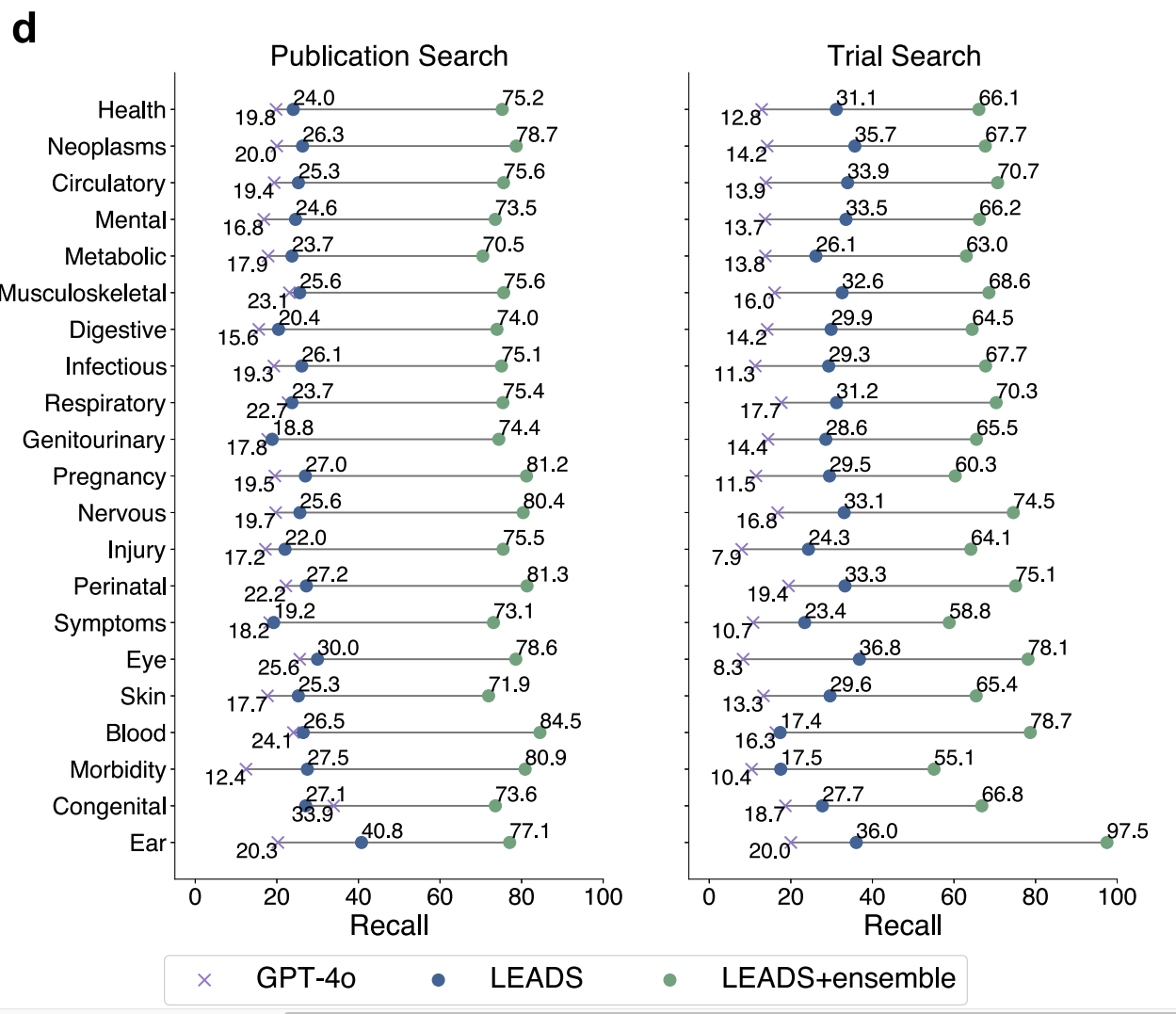

Once we had this pipeline, the next question was obvious: how far can we go with off-the-shelf models like GPT-4o, and when do we need something more specialized? One concrete stress test was the very first step: search. When we measured the recall of search strategies proposed by GPT-4o for real systematic reviews, we saw a problem. A single GPT-generated query could miss around 80 percent of the studies that the human review had actually included. For clinical guidelines, that is not just a small degradation. That is a nonstarter.

In TrialMind-SLR, we partially fixed this through ensembling: ask the model for multiple diverse query formulations, run them all, and merge the results. That alone pushed recall up to around 80 percent, which is much closer to what you need for serious evidence synthesis. But this experience also told us something deeper. Open-box LLMs are incredibly capable, but if you want them to behave like a well-trained evidence librarian, you cannot just prompt harder. You need to train them for the job. That is where LEADS comes in [2], our paper recently published in Nature Communications.

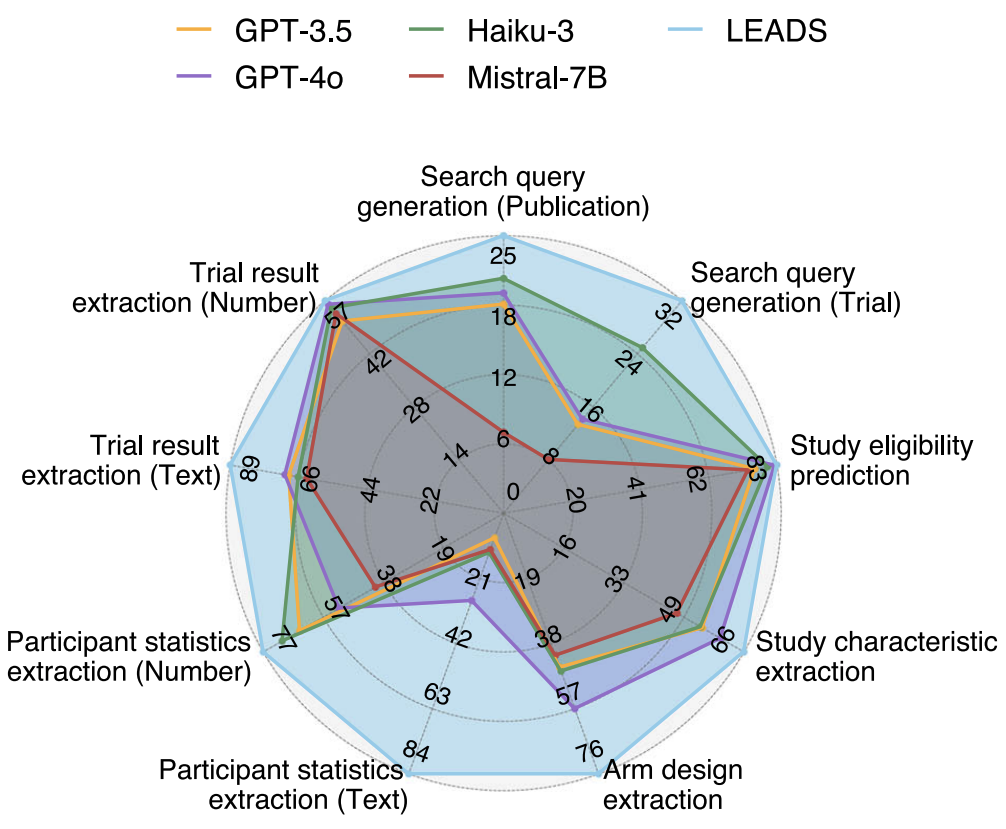

LEADS is our foundation model for medical literature mining, trained specifically on PubMed-scale data for SLR-style tasks. We harvested around twenty thousand systematic reviews and more than four hundred thousand clinical trials, then built supervised and reinforcement learning signals on top of them. The goal was to teach a relatively compact 7-billion-parameter model to behave like a domain expert when it comes to search, screening, and extraction, rather than a general conversational assistant.

The fun part is that LEADS beats GPT-4o on many of these tasks, despite being much smaller and trained only on public biomedical data. That suggests that there is real headroom in vertical models that are aligned to the "boring" but critical parts of clinical SLRs, even if big general models have probably already seen most of the same documents in pretraining. With a better algorithm, like we tried in DeepRetrieval [3] using reinforcement learning to train LLMs to do PubMed search, the improvement can be more significant.

So Where Do AI Agents and Deep Research Fit In?

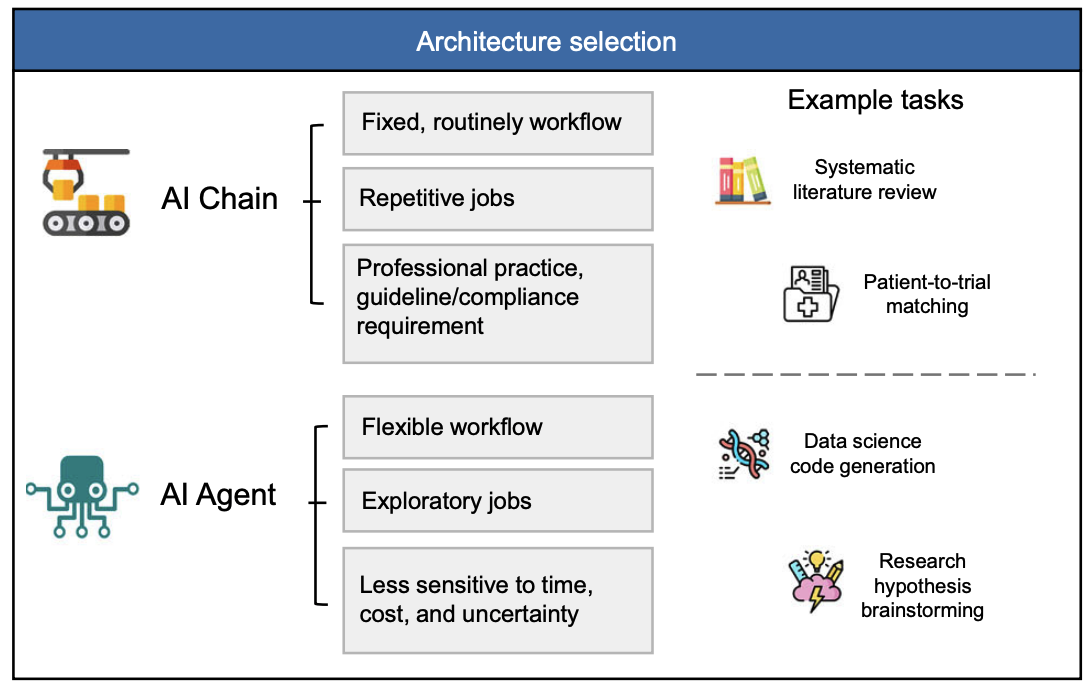

Let us go back to that original intuition: agents feel powerful because they can autonomously explore, iterate, and use lots of test-time compute. That "scaling of test-time inference" idea is real. If you let an agent try multiple search paths, critique its own reasoning, and refine its queries, you often get better answers. The catch, in medicine, is control.

Real systematic reviews need stable data sources, clear documentation of every search and screening decision, and a way for humans to inspect and reproduce the pipeline. Many current agent systems are optimized for flexibility and exploration, not for auditability. Their data sources can include web pages of uncertain provenance. Their internal hops are rarely logged in a way that a journal editor or regulator would accept.

So our view is not that agents are bad for SLRs. It is that they need to be grounded. You want the autonomy and test-time exploration of agents, but inside a scaffold that looks a lot like TrialMind-SLR and powered by models like LEADS that are trained for clinical literature rather than general chat. That is the space we are actively exploring now: how to plug agentic behaviors into a workflow that still respects PRISMA, keeps everything reproducible, and remains usable in regulated contexts.

If you remember only one thing, make it this: searching and summarizing papers is the easy part. For medicine, the real challenge is turning LLMs into dependable partners in the painstaking, rule-bound machinery of evidence-based practice. TrialMind-SLR shows that you can turn the SLR pipeline into an LLM-friendly workflow [1]. LEADS shows that a focused, domain-trained model can outperform massive general models on those workflow tasks [2]. The next step is to bring in agents without losing the rigor that makes systematic reviews worth trusting in the first place.

References

[1] Zifeng Wang, Lang Cao, Benjamin Danek, Qiao Jin, Zhiyong Lu, & Jimeng Sun. (2025). Accelerating clinical evidence synthesis with large language models. npj Digital Medicine, 8(1), 509.

[2] Zifeng Wang, Lang Cao, Qiao Jin, ... & Jimeng Sun. (2025). A foundation model for human-ai collaboration in medical literature mining. Nature Communications, 16(1), 8361.

[3] Pengcheng Jiang, Jiacheng Lin, Lang Cao, ... & Jiawei Han. (2025). DeepRetrieval: Hacking real search engines and retrievers with large language models via reinforcement learning. Second Conference on Language Modeling (CoLM).

[4] Zifeng Wang, Hanyin Wang, Benjamin Danek, ... & Jimeng Sun. (2025). A perspective for adapting generalist AI to specialized medical AI applications and their challenges. npj Digital Medicine, 8(1), 429.