December 11, 2025 · Zifeng Wang, PhD, Keiji AI

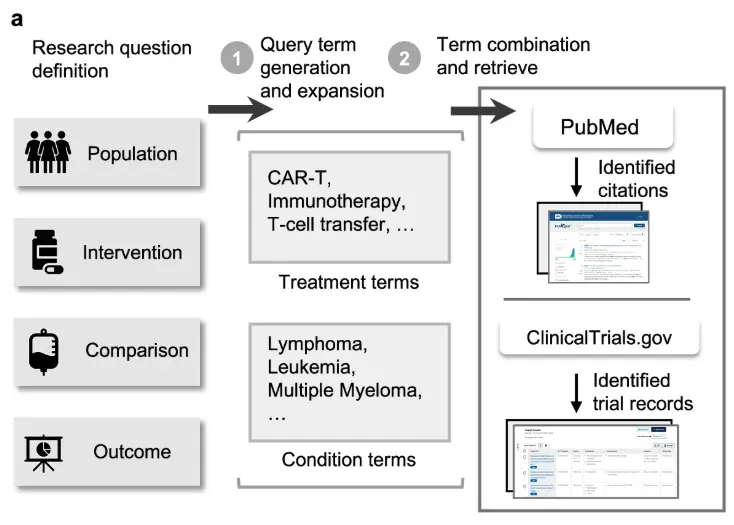

Sifting through massive biomedical literature is a headache. Anyone who has opened PubMed for a systematic review knows this feeling. Yes, agentic AI systems like ChatGPT DeepResearch have shown that LLMs can browse the open web and summarize information from many places. But biomedical literature is different. We care about high-quality evidence from published studies, clinical trials, curated databases. And these sources come with highly structured, sometimes painfully complex search fields that generic LLMs rarely understand out of the box.

This is exactly where we found an opportunity. LLMs can do literature search, but only if you teach them with vertical, domain-specific data and the right form of post-training.

Supervised Fine-Tuning and Reinforcement Learning

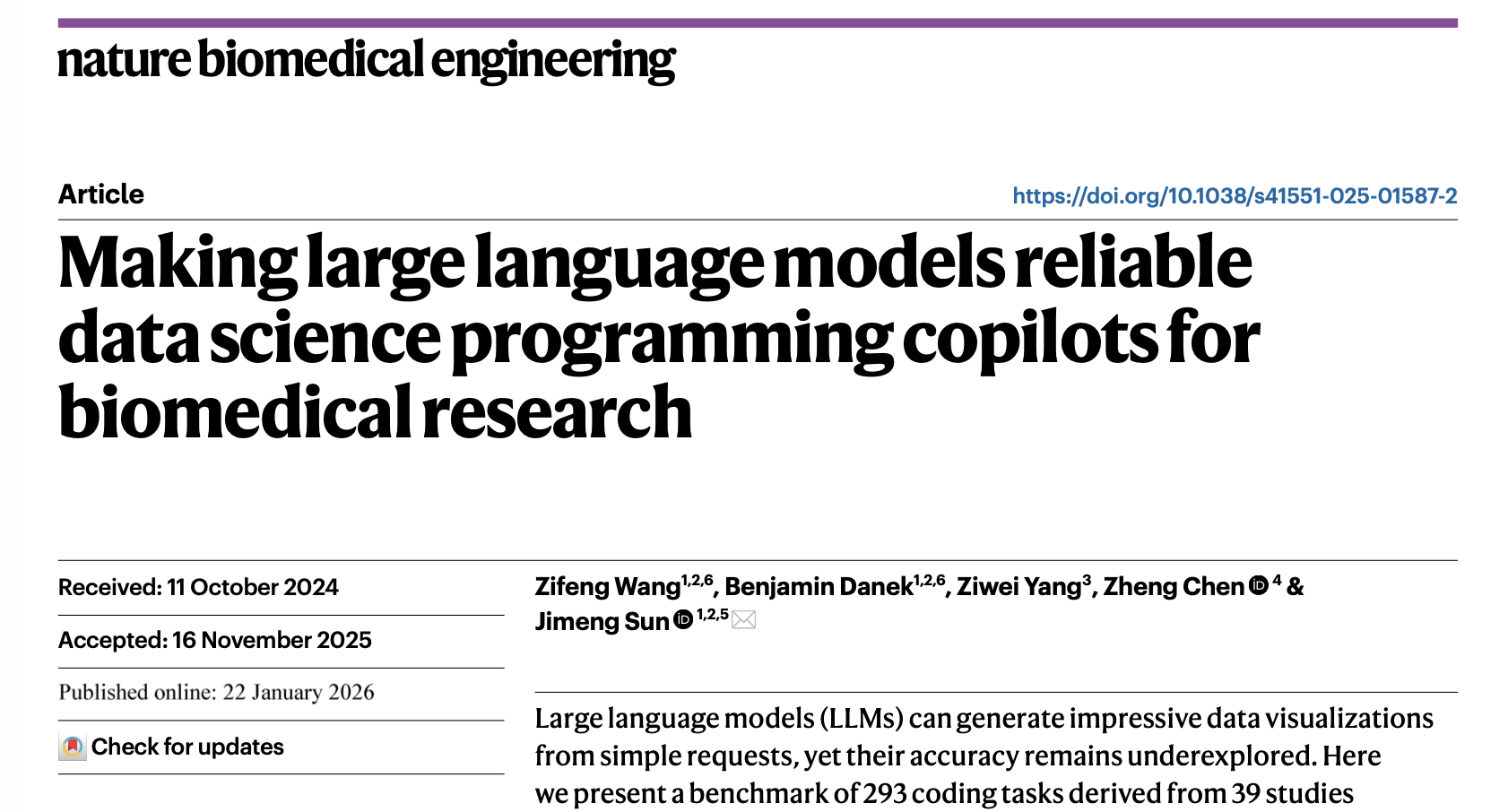

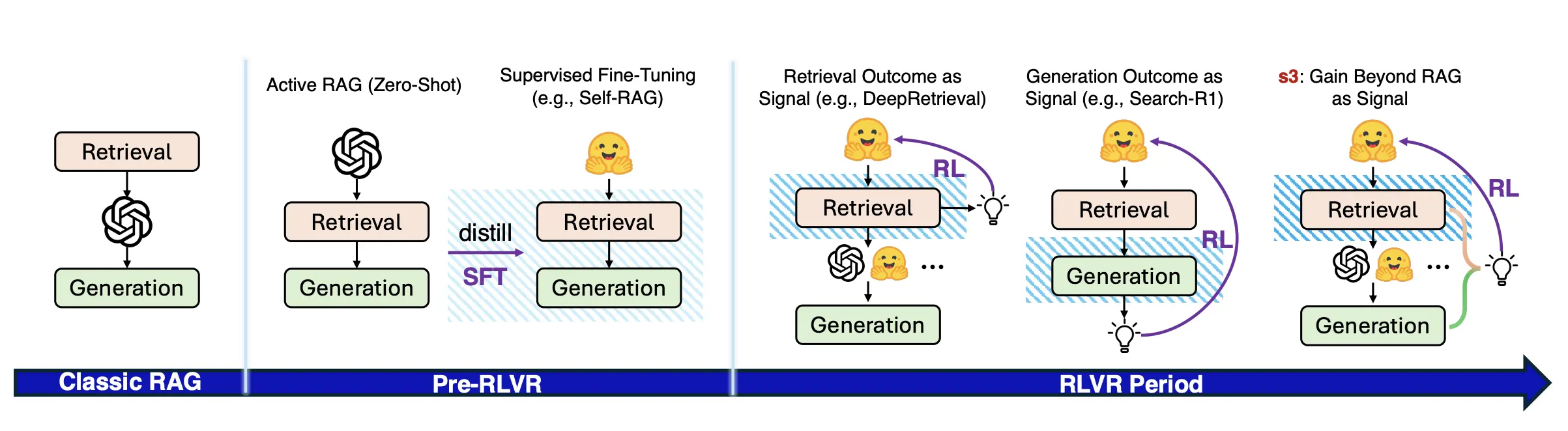

Before we get to the fun part, it helps to clear up what supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and Reinforcement Learning (RL) actually are in this context. Both are post-training methods, meaning they operate after the model has already consumed the web-scale pretraining corpus. Pretraining gives an LLM memory. Post-training teaches it how to use that memory to solve tasks.

Imagine a model that has read the entire Internet but has never practiced answering a specific clinical question. It knows words, patterns, facts, but it doesn't yet know the procedure of solving the problem you care about. Post-training is how we instill that procedure.

SFT is the intuitive one. You give the model an input and the ideal output, such as a question and the correct answer. Then you train it to mimic that answer token by token. It sounds too simple, but mysteriously, it generalizes. You can train on a few thousand examples of PubMed query construction and the model starts performing decently on completely new topics. Of course, "completely new" is always in quotes because the model has probably seen related material during pretraining, just not in the structured way you expose during SFT.

Reinforcement learning, especially RLVR (RL with verifiable rewards), changes the game. This is the approach that powered the new wave of reasoning models like DeepSeek R1. Instead of copying an example, the model behaves like an agent exploring actions, receiving rewards based on whether it gets the answer right or wrong. The crucial part is designing a reward that is objectively verifiable. Math is the classic example. But as we show, search quality for literature can also be turned into a verifiable signal.

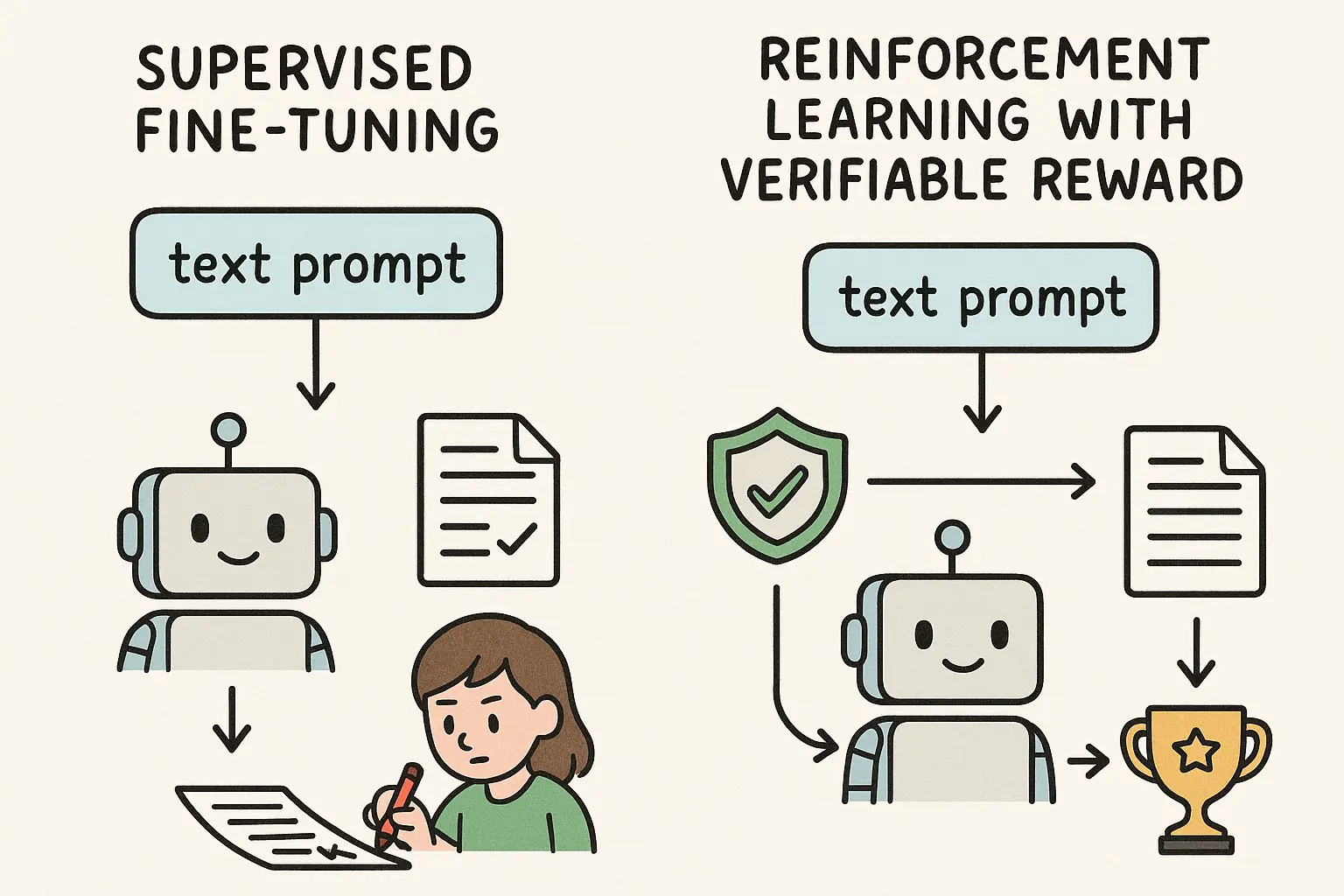

LEADS: Vertical Data and Supervised Fine-Tuning for Making Search Queries

Here is the first problem you run into when you ask an LLM to help search PubMed. You have to prompt it with a clinical question and expect it to produce a valid Boolean query with the right operators, MeSH terms, filters, and logic. These queries are often longer than the abstract you're trying to retrieve. Even cutting-edge models struggle.

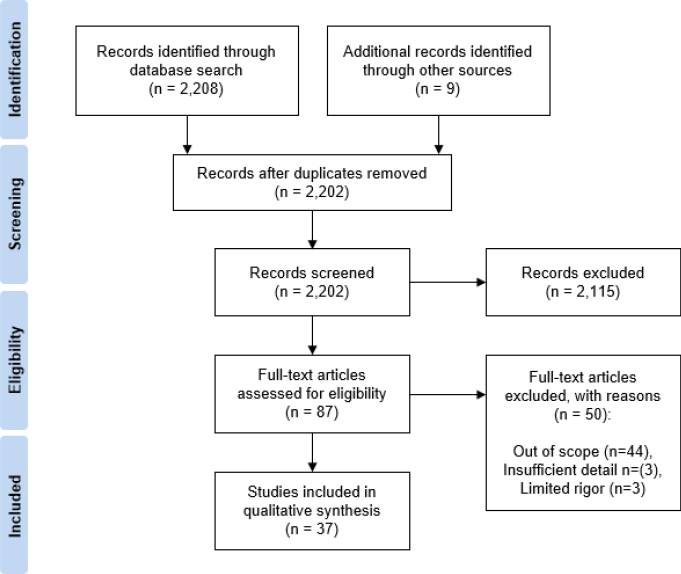

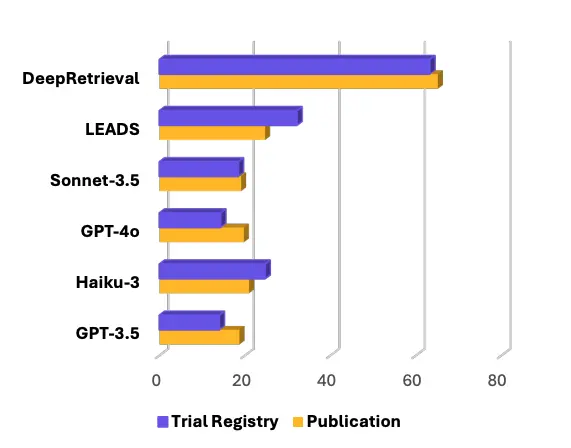

In our Nature Communications paper LEADS [1], we evaluated GPT-4o on systematic review search reproduction. For every review, we took the review's research objective, asked the model to generate a search query, ran it against PubMed, and checked whether the included studies from the original review were retrieved. The overlap was tiny.

LEADS is an LLM trained on tens of thousands of review-question to search-query examples using SFT. The setup is simple: input is the PICO-style review question, output is the search query used to find the relevant studies. By training directly on vertical data, we enabled a 7B-parameter model to outperform GPT-4o on systematic-review-style search tasks.

DeepRetrieval: Reinforcement Learning for Literature Search

SFT got us far, but not far enough. The core limitation was that high-quality labeled queries simply do not exist. Review papers list the included studies but rarely publish the exact queries that produced them. So in our earlier work, we resorted to sampling many candidate queries and keeping the best ones as pseudo-labels. That was tedious and noisy. Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Reward (RLVR) changed everything.

In our CoLM paper DeepRetrieval [2], we built an RL framework where the model itself proposes a query, sends it to the PubMed API, retrieves the results, and earns a reward proportional to how many target studies it successfully recalls. No ground truth query needed. The only ground truth is whether the target studies appear.

Once we flipped the training into this verifiable-reward setup, performance jumped. DeepRetrieval strongly improved recall on PubMed search tasks and even on clinical trial searches in ClinicalTrials.gov. In head-to-head comparisons, it surpassed LEADS and proprietary models like Sonnet-3.5 on systematic-review-style recall. This was our first demonstration that LLMs can be trained into effective domain search engines without ever seeing an annotated query.

s3: Multi-Turn Search Agents

DeepRetrieval was powerful but still had a limitation. It was one-shot. If the model produced a bad query, that was it. Humans don't search like that. We check the results, refine the query, try again, explore different angles, then merge what we found.

So we extended the idea to s3 [3], published at EMNLP 2025, adding the missing ingredient: multi-turn interaction. The model does not just propose a single query. It sees the results, adjusts, searches again, and continues until it converges on high-quality evidence. The reward function evaluates both intermediate search quality and the final answer, which can be a synthesized evidence summary. This makes s3 a true agentic AI searcher. Not just a query generator, but a reasoning loop. A small glimpse of what robust literature agents will look like.

Discussion

If you zoom out, the trend is clear. Agentic AI searchers are the future of biomedical knowledge discovery. PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov are already challenging for generic LLMs, and these are still text-based systems. The real frontier involves ontologies, biochemical knowledge graphs, protein databases, multimodal molecular repositories. Searching UniProt or KEGG or PubChem requires understanding structured schemas and relational semantics far beyond free text. Generic LLMs simply do not have that capability. Not yet.

The path forward is vertical training: supervised fine-tuning, reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards, and multi-turn agent architectures that actually explore and reason. At Keiji AI, we are committed to pushing this frontier, developing agents that can navigate the full biomedical data ecosystem and support clinicians, scientists, and researchers in ways previously impossible. And this is still only the beginning.

References

[1] Zifeng Wang, Lang Cao, Qiao Jin, … & Jimeng Sun. (2025). A foundation model for human-ai collaboration in medical literature mining. Nature Communications, 16(1), 8361. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-62058-5

[2] Pengcheng Jiang, Jiacheng Lin, Lang Cao, … & Jiawei Han. (2025). DeepRetrieval: Hacking real search engines and retrievers with large language models via reinforcement learning. Second Conference on Language Modeling (CoLM). https://openreview.net/pdf?id=u9JXu4L17I

[3] Pengcheng Jiang, Xueqiang Xu, Jiacheng Lin, Jinfeng Xiao, Zifeng Wang, Jimeng Sun, and Jiawei Han. 2025. s3: You Don't Need That Much Data to Train a Search Agent via RL. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). https://aclanthology.org/2025.emnlp-main.1095/