November 18, 2025 · Zifeng Wang, PhD, Keiji AI

If you have been online lately, you have probably noticed something. Everything starts to sound like it was written by a large language model. Emails, essays, peer reviews, even grant proposals. We are not here to judge any of that. Let us talk about something more specific and frankly more consequential: using AI to draft clinical trial documents.

At first glance this seems like a low hanging fruit. After all, clinical trials are full of text: protocols, informed consent forms, statistical plans. Give the model enough material and it should be able to write something useful. Right? Well, not quite. Anyone in this space will tell you that generic AI models struggle in highly specialized domains like clinical trials. They do not know what to retrieve. They improvise details that should never be improvised. They forget that regulators exist.

So our journey started not with a giant generative model, but with something more humble and necessary. Retrieval. Let us rewind to the very beginning.

Trial2Vec: The First Building Block of Retrieval

Back in 2021 and 2022, before generative AI took over everyone's feeds, we were obsessed with one question. Could we build a representation of clinical trials that actually understands what a trial is about? Not just the words on the page, but the medical meaning behind them.

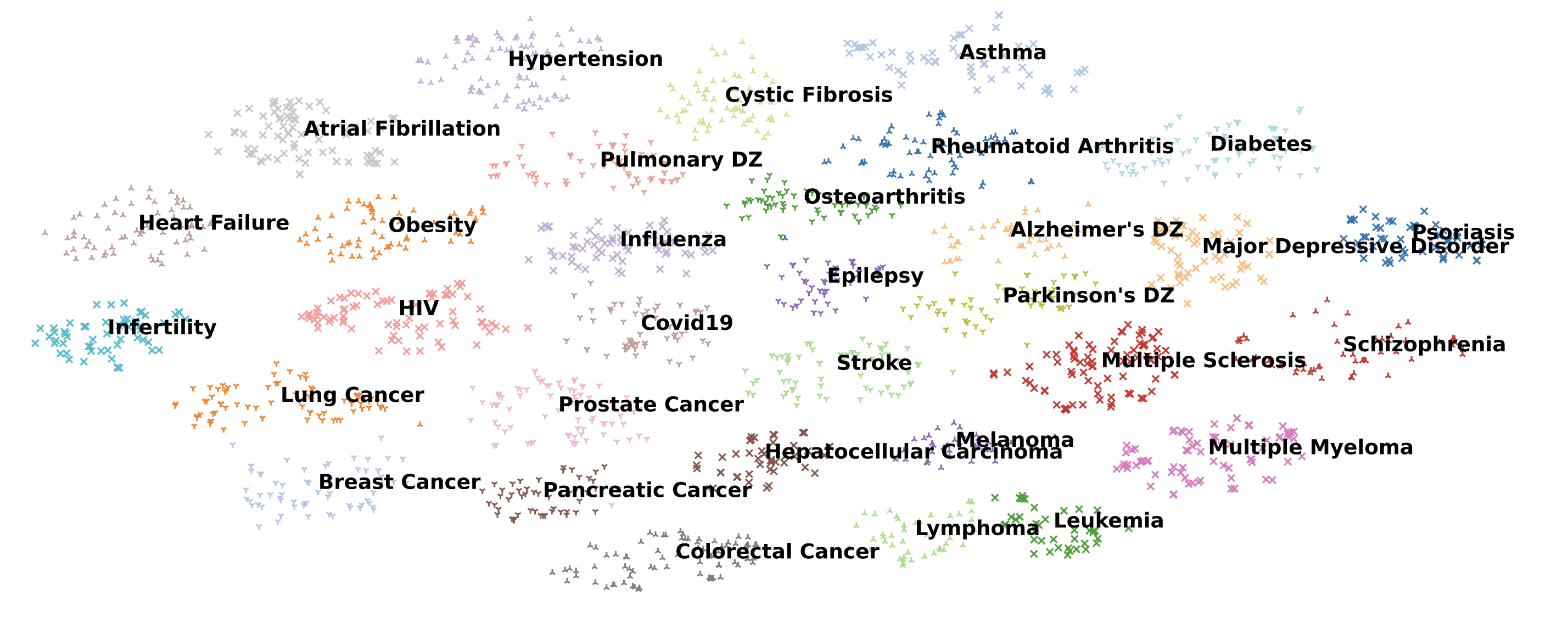

That became Trial2Vec [1]. Think of it as a way to turn every trial synopsis from ClinicalTrials.gov into a point in a giant map. Similar trials end up close together. Very different trials drift apart. We trained a BERT model on four hundred thousand trial descriptions using self supervision. The idea was playful. Take a trial synopsis, mix one component with another trial, and force the model to tell which version is real. Over tens of thousands of these perturbations, it learned the shape of trial space.

Plot these embeddings into two dimensions and you start to see neighborhoods. Oncology trials cluster one way. Cardiology another. Device trials settle somewhere else. Suddenly retrieval becomes a superpower. Instead of keyword search, you can ask: show me trials like this one. That core idea ends up powering everything that came next.

AutoTrial: Adding RAG So Models Can Write More Sensibly

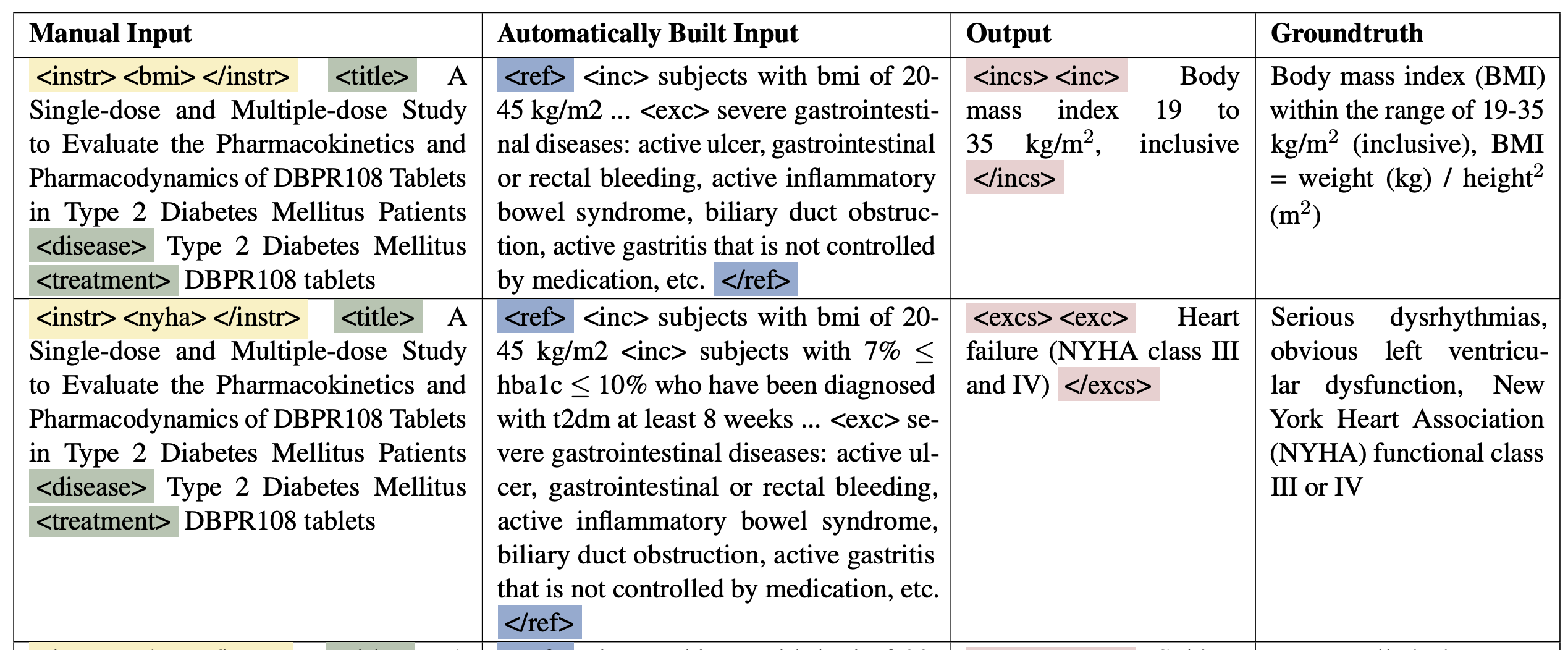

Fast forward to 2022. ChatGPT had not yet arrived, so everyone was still working with early GPT style models. We wanted to see if a model could draft trial eligibility criteria. We developed a system called AutoTrial [2]. The plan sounded simple. Give the model a trial description. Ask it to produce one criterion. Train it on thousands of examples. What could go wrong?

Everything. It turns out that without hints, a model at that time could not reliably write criteria. The output was vague or generic or simply wrong. The breakthrough came when we combined the generator with retrieval. Instead of a blank canvas, we first gave it the target concept, like BMI, then fetched similar trials using Trial2Vec, then extracted their BMI related criteria. Now the model had concrete examples and could generalize from them. That was the moment we realized retrieval augmented generation was not just helpful. It was essential.

Panacea: Fine-Tuning Large Language Models as Trial Foundation Models

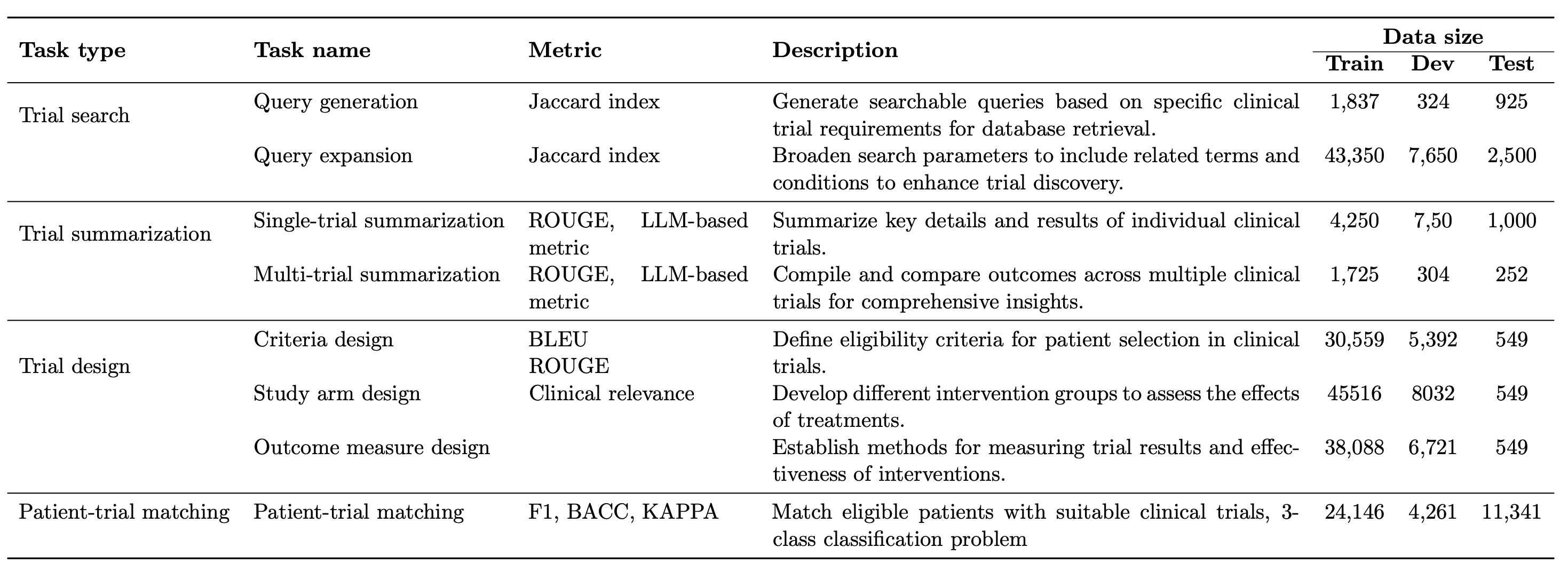

By 2023 the generative models had grown teeth. Llama and others made it finally possible to train specialized models without needing a supercomputer. So we asked: what would a foundation model look like if it were raised entirely on clinical trial knowledge?

This became Panacea [3]. One million trial synopses went into creating supervised instruction data. We taught the model how to design criteria, define study arms, infer outcomes, and summarize trials. The surprising part was not just that it worked. Panacea outperformed every open source model we could find and approached GPT four level performance on many tasks. All with seven billion parameters. It made one thing clear. When you give a model structured domain knowledge, it learns faster and wastes less capacity on irrelevant patterns from the general web.

InformGen: Agentic AI Drafting with Retrieval and Foundation Models

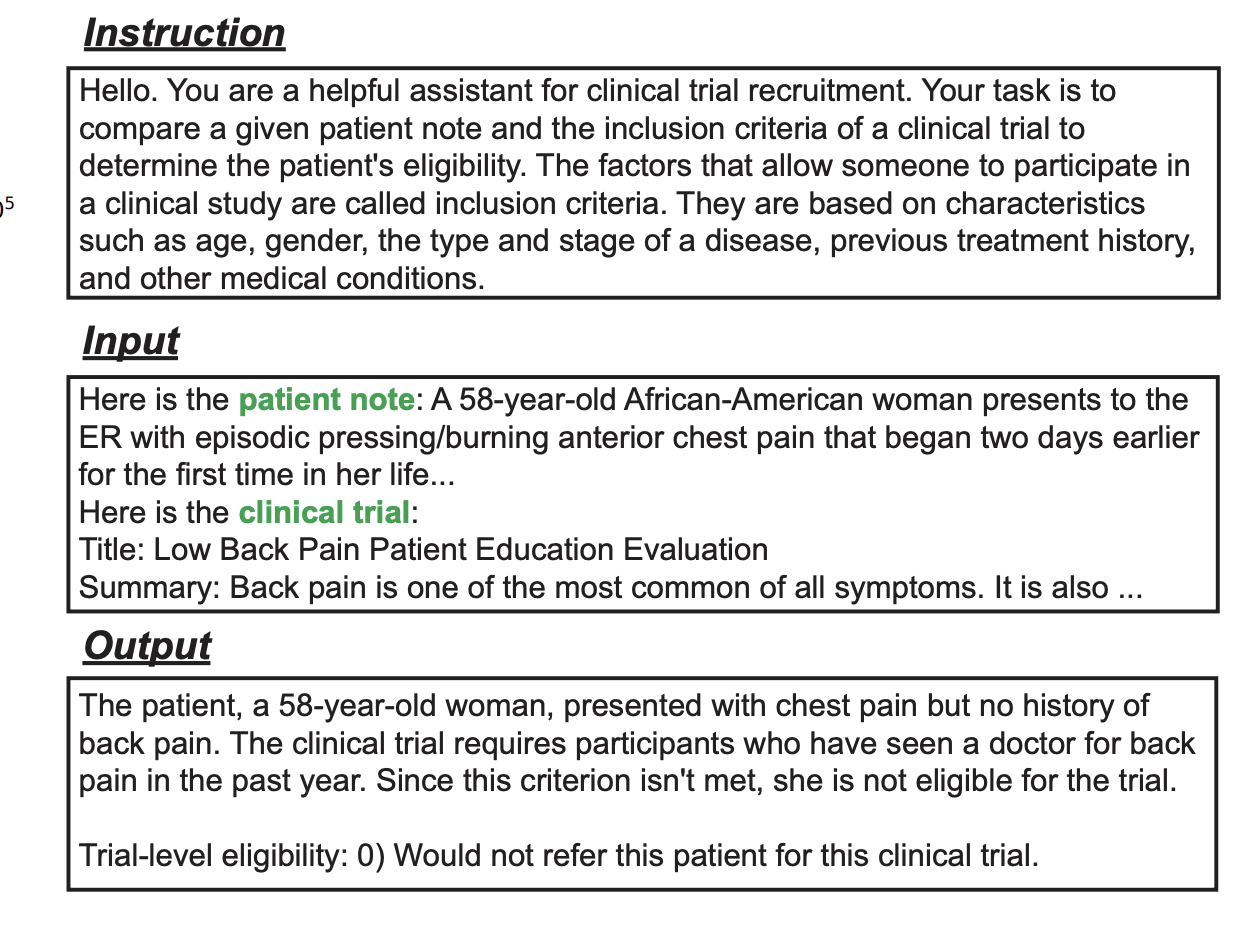

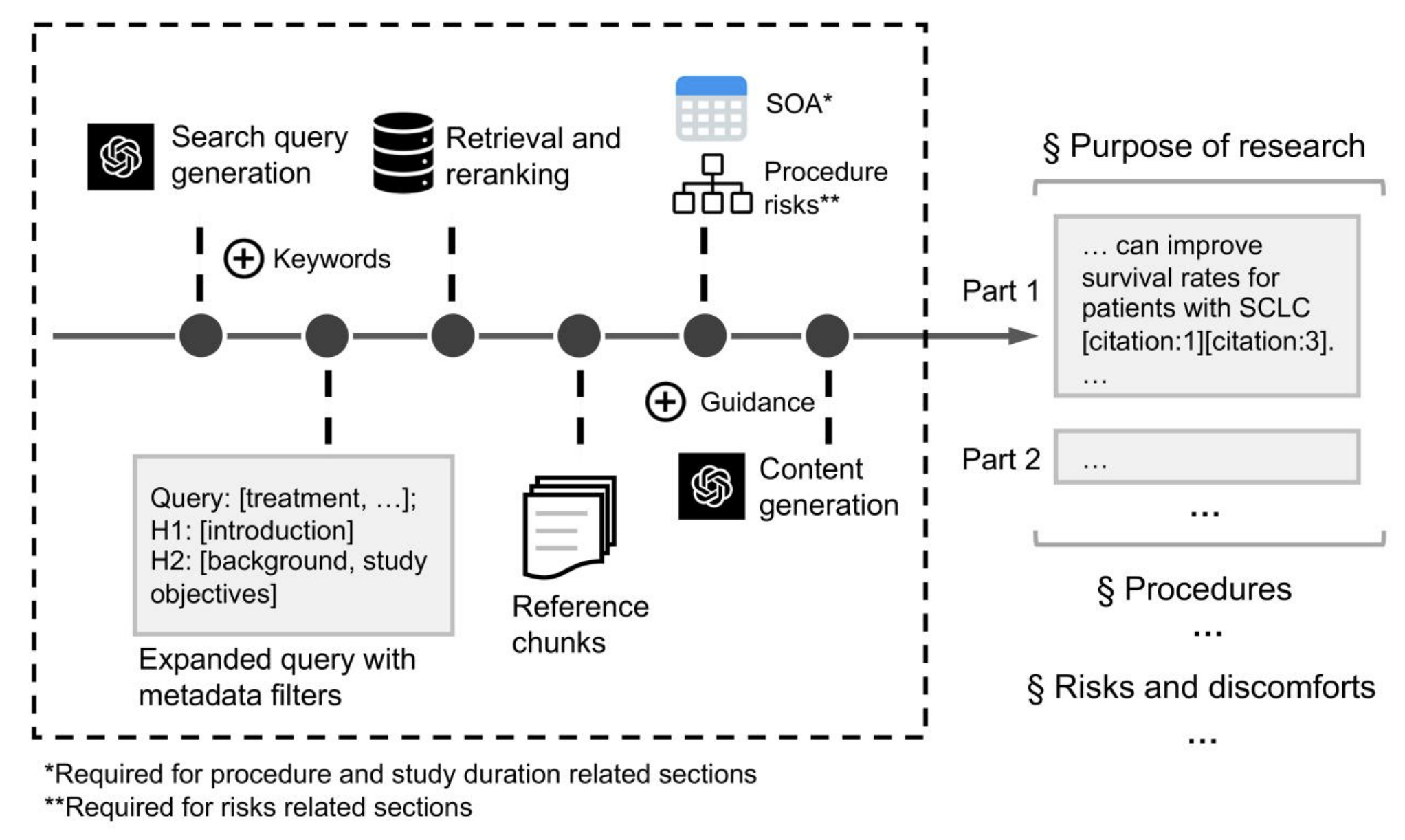

Now we arrive at 2024, the year everyone started talking about agents. The original promise is simple. Instead of asking a model to do one giant task in a single pass, let it break down the job into smaller steps and loop until it gets it right. For clinical trial documents, which can stretch to hundreds of pages, this is the only viable path.

In InformGen [4], we built an agentic workflow that takes a long protocol and produces a complete informed consent form section by section. At each step the agent retrieves supporting text from the protocol, uses our trial tuned LLM to draft a section, evaluates whether it followed the template, and tries again if needed. Retrieval keeps it grounded. The trial foundation model keeps the writing domain aware. The agent loop lets it improve iteratively.

It is no longer a single model call pretending to know everything. It is more like a junior medical writer with access to a library and the ability to revise drafts quickly.

The Catch: Reliability and Validation

Now here is the twist. Even with retrieval, and even with a strong foundation model, the outputs can still go wrong. In our JAMIA study [4], even GPT four zero occasionally wrote ICF content that violated FDA guidance or invented treatment schedules. In clinical research, that is not a small mistake. It is a deal breaker.

This forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth about generative AI for regulated domains. Generating text is easy. Validating text is the real bottleneck. The moment an AI writes something that looks polished, people stop checking it as rigorously as they should. So the real design challenge is not better generation. It is better guardrails. Better retrieval traces. Better human in the loop review triggers. Better tools to highlight risky sections before they get copied into a live document.

Where We Go From Here

If the first phase of AI was about generation, the second phase is about judgment. In clinical trials, we need systems that not only write but also explain, verify, and cite. We need agentic workflows that know when they are uncertain and call for human attention. We need models that understand regulatory boundaries instead of hallucinating around them.

RAG helped. Fine tuning helped. Agent loops helped even more. But the future belongs to AI that can draft and validate, not just draft faster.

And that is where our work continues.

References

[1] Wang, Zifeng, and Jimeng Sun. "Trial2Vec: Zero-Shot Clinical Trial Document Similarity Search using Self-Supervision." 2022 Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022. 2022.

[2] Wang, Zifeng, Cao Xiao, and Jimeng Sun. "AutoTrial: Prompting Language Models for Clinical Trial Design." The 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

[3] Jiacheng Lin, Hanwen Xu, Zifeng Wang, Sheng Wang, Jimeng Sun. (2024). Panacea: A foundation model for clinical trial search, summarization, design, and recruitment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.11007.

[4] Zifeng Wang, Junyi Gao, Benjamin Danek, Brandon Theodorou, Ruba Shaik, Shivashankar Thati, Seunghyun Won, Jimeng Sun, Compliance and factuality of large language models for clinical research document generation, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 2025;, ocaf174, https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaf174