February 10, 2026 · Zifeng Wang

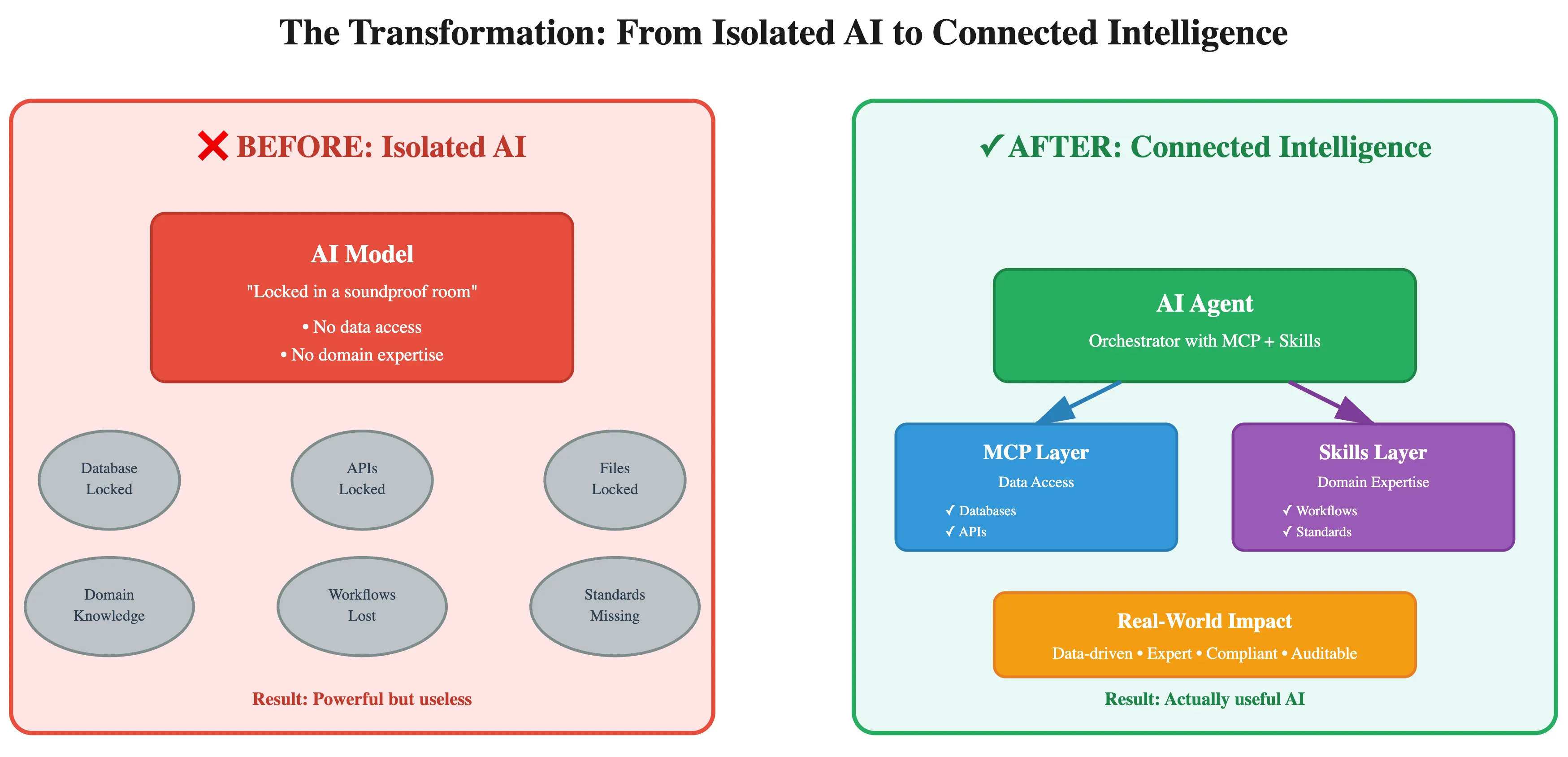

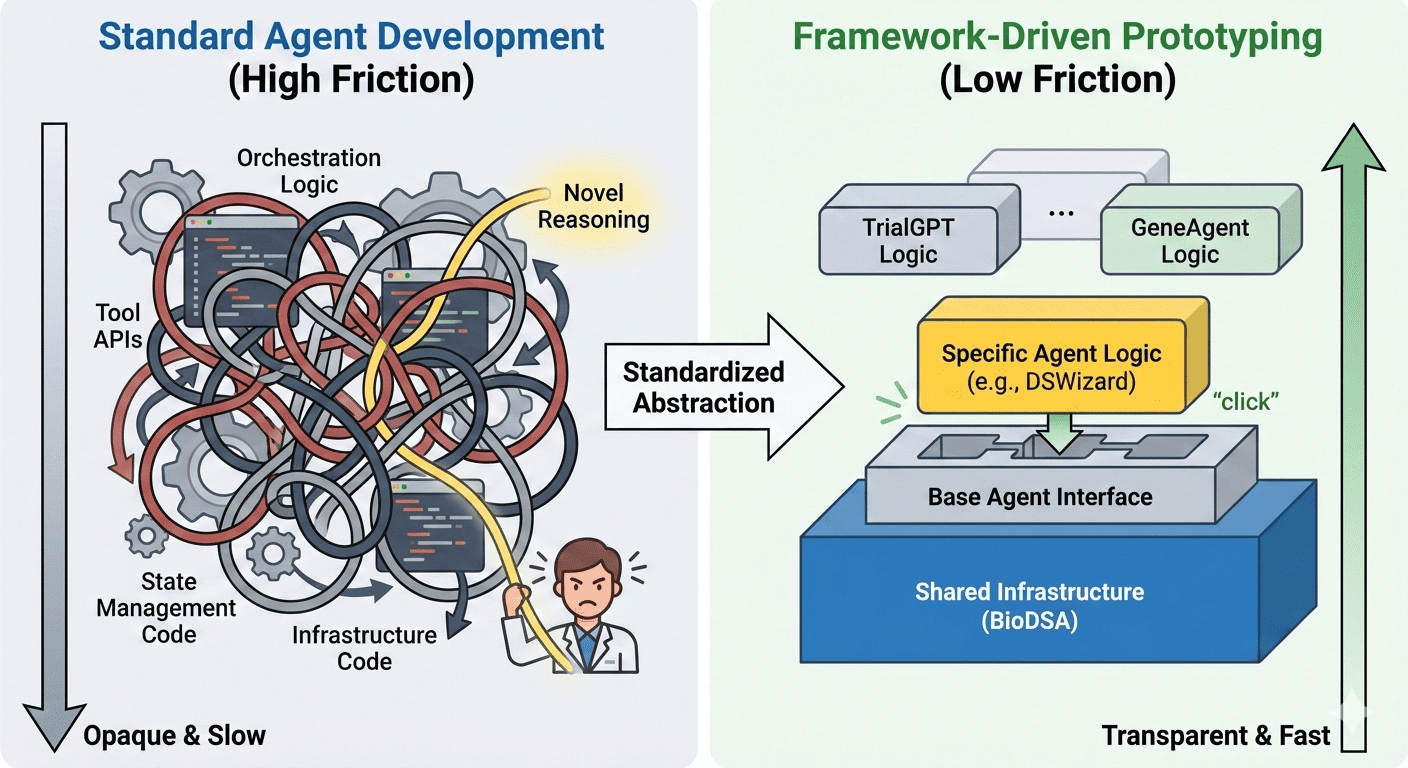

Recently, a Nature Machine Intelligence editorial [1] highlighted a growing challenge in the development of AI agent systems: increasing complexity without increasing transparency. Modern agent frameworks often involve layered orchestration logic, extensive tool ecosystems, memory modules, and complex computational graphs. While these architectures promise powerful capabilities, they frequently introduce a new barrier — researchers and practitioners struggle to understand where to begin when building their own agents.

This problem strongly resonates with our experience in biomedical AI research. Despite the rapid growth of multi-agent systems across scientific domains, reproducing or extending existing agents remains surprisingly difficult. Many implementations are tightly coupled to specific infrastructures, rely on undocumented assumptions, or require substantial engineering effort before meaningful experimentation can even start. For researchers who want to explore new ideas — or simply benchmark existing methods — the starting point is often unclear.

So we asked a simple question: How easy should it be today to prototype a specialized AI agent? To explore this, we ran a practical experiment attempting to reproduce multiple biomedical AI agents within a single day.

A One-Day Experiment: Reproducing Eight AI Agents

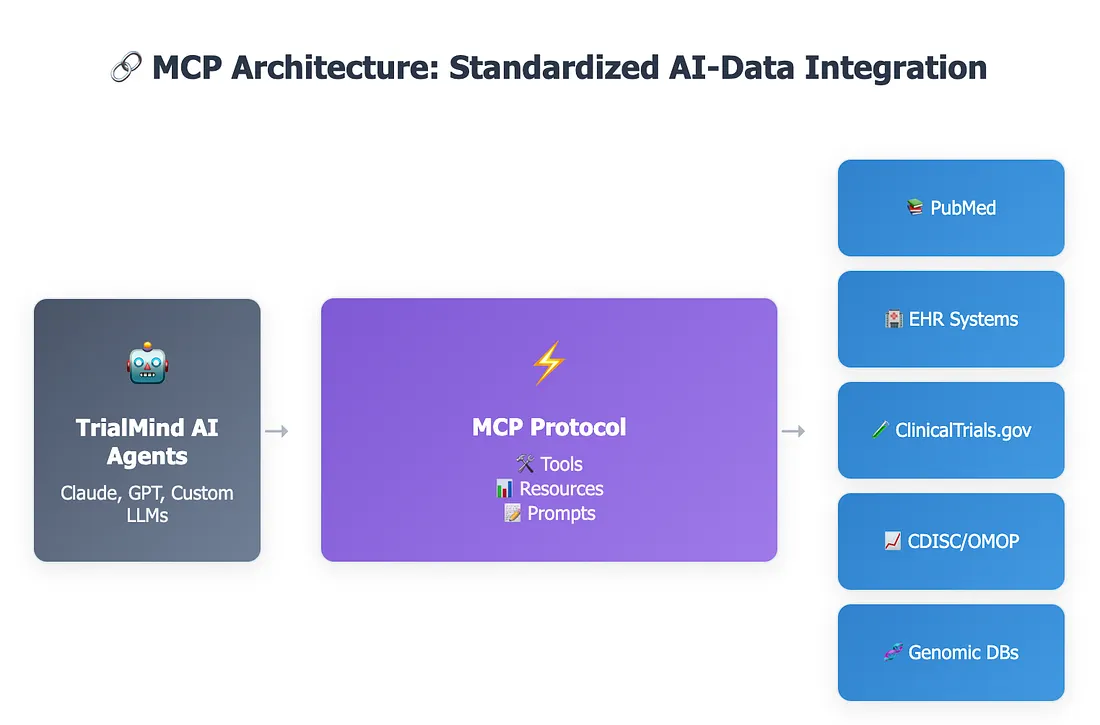

Using our BioDSA open-source framework (GitHub) [2], we attempted to reproduce a diverse set of biomedical AI agents by providing their research papers to a Cursor-based coding workflow and manually validating the resulting implementations.

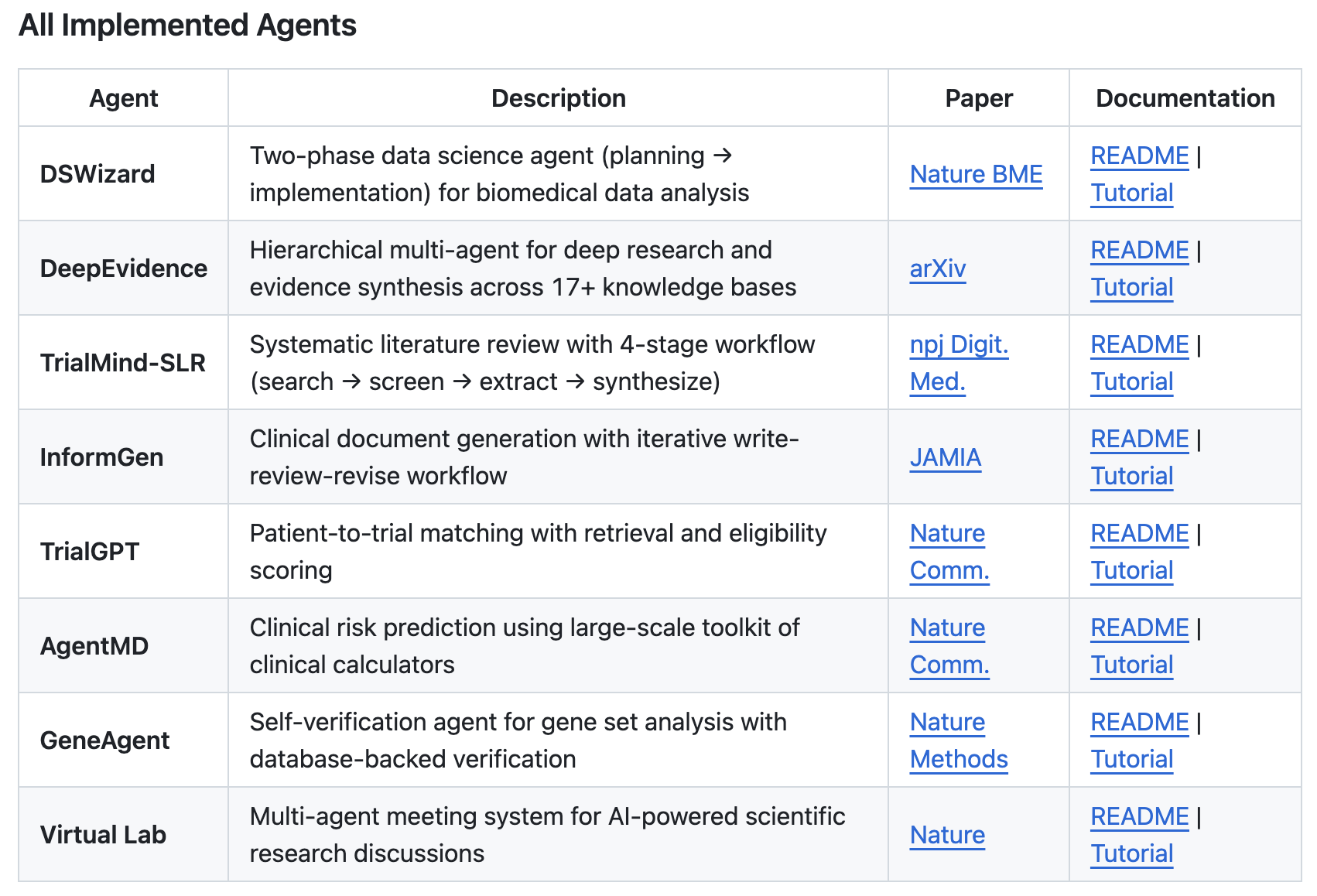

Within one day, we reproduced eight different agents spanning a wide range of scientific workflows: DSWizard [3], a two-phase planning-and-implementation data science agent; DeepEvidence [4], a hierarchical multi-agent system for deep research and evidence synthesis across biomedical databases; TrialMind-SLR [5], a structured systematic literature review workflow; InformGen [6], an iterative clinical document generation agent; TrialGPT [7], for patient-to-trial matching via retrieval and eligibility scoring; AgentMD [8], for clinical risk prediction using calculator-based tools; GeneAgent [9], featuring self-verification workflows for gene set analysis; and Virtual Lab [10], a multi-agent scientific discussion system.

The surprising outcome was not simply that these agents could be reproduced — but that they could be implemented rapidly once the right scaffolding existed. Instead of reinventing orchestration logic each time, we relied on a shared framework providing template base classes for single-agent and multi-agent systems, built-in tool interfaces, structured planning workflows, memory and context handling, and standardized execution pipelines. In other words, the heavy engineering work had already been solved, fundamentally changing the development experience.

The Real Bottleneck Is Not Intelligence — It's Architecture Friction

Many AI agent publications emphasize novel reasoning techniques or advanced prompting strategies. However, in practice, the biggest obstacle we encountered was neither reasoning nor model capability — it was implementation complexity.

Common issues include agent logic tightly intertwined with infrastructure code, non-standardized tool APIs, implicit state handling across multiple steps, custom orchestration patterns that are difficult to generalize, and the absence of reproducible benchmarking pipelines. These challenges slow experimentation and discourage exploration; researchers often spend more time building scaffolding than testing hypotheses.

Ironically, this creates a paradox: while agent research aims to accelerate workflows, developing agents themselves can become slow and opaque.

BioDSA: Designing for Rapid Agent Prototyping

The BioDSA framework originated from challenges encountered during the development of DSWizard [3] (Nature Biomedical Engineering), where rapid experimentation across multiple agent designs was essential.

The core philosophy is simple:

Every new agent should feel like implementing a new class — not building a new system.

Rather than defining agents as monolithic applications, BioDSA treats them as modular components:

from biodsa.agents import BaseAgent

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, END

class MyCustomAgent(BaseAgent):

# Step 1: Inherit BaseAgent for LLM, sandbox, tools

def _create_agent_graph(self):

# Step 2: Define your workflow as a state graph

workflow = StateGraph(AgentState)

# Step 3: Add nodes (each node is a function)

workflow.add_node("step_1", self._first_step)

workflow.add_node("step_2", self._second_step)

# Step 4: Connect nodes with edges

workflow.add_edge("step_1", "step_2")

workflow.add_edge("step_2", END)

workflow.set_entry_point("step_1")

# Step 5: Compile and return

return workflow.compile()

def go(self, query: str):

return self.agent_graph.invoke({"messages": [query]})Once defined, the agent automatically inherits execution environment setup, tool registry integration, memory management, logging, and benchmarking hooks. This abstraction allows researchers to focus on what actually matters — workflow design, reasoning strategies, and evaluation experiments — rather than infrastructure engineering.

Transparency Through Structure

Reproducing multiple agent systems revealed several important insights.

First, despite differences in domain and implementation, most agents share similar structural patterns — planning, tool use, verification or reflection, and iterative refinement. Recognizing these shared patterns makes it possible to standardize implementation.

Second, framework design directly determines experimentation speed. When infrastructure is reusable, implementing a new agent becomes an incremental task rather than a large engineering project, significantly lowering the barrier to exploring new ideas.

Third, benchmarking becomes easier when execution is standardized. Because all agents inherit the same execution interface, consistent evaluations can be run across datasets, prompts, model backends, and workflows. This helps address one of the major concerns raised in recent editorials [1]: lack of transparency and reproducibility.

Modern agent systems often appear opaque not because of complexity itself, but because that complexity is hidden behind inconsistent abstractions. Structured frameworks can improve transparency rather than reduce it. By standardizing planning stages, tool invocation patterns, memory updates, and evaluation checkpoints, agent behavior becomes easier to inspect and compare. Instead of reverse-engineering hidden logic, researchers can simply read a subclass definition and understand how the agent operates.

How Easy Is It Today to Prototype a Specialized AI Agent?

The ease of prototyping AI agents today depends largely on tooling. Without structured frameworks, implementing new agent systems remains difficult due to fragmented architectures, hidden orchestration logic, and inconsistent evaluation workflows. However, with well-designed abstractions, building specialized agents can shift from a multi-week engineering effort to a rapid process completed in hours or days.

In our recent experiment, we reproduced multiple published agents by providing research papers to an AI coding assistant, mapping their workflows onto standardized agent templates, implementing domain-specific logic, manually validating outputs, and running unified benchmarks. This structured workflow enabled rapid iteration and systematic experimentation that would have been impractical without reusable infrastructure.

As AI agent systems continue to evolve, the field may benefit from shared engineering principles: standardized agent interfaces, reusable orchestration patterns, transparent execution traces, benchmark-driven evaluation, and modular tool ecosystems. Similar to how deep learning advanced through common frameworks such as PyTorch and TensorFlow, agent research may progress faster through unified infrastructures designed for experimentation rather than deployment complexity.

BioDSA reflects this philosophy by automatically exporting execution reports for every run, allowing researchers to review reasoning steps, tool calls, and outputs without digging through logs. Our experience suggests that the main challenge is not agent complexity itself — but whether our development tools and abstractions have kept pace. When they do, prototyping becomes accessible, transparency improves, and meaningful experimentation accelerates.

References

[1] Multi-agent AI systems need transparency. Nat. Mach. Intell. 8, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-026-01183-2

[2] BioDSA. Biomedical Data Science Agents. GitHub repository: https://github.com/RyanWangZf/BioDSA; project site: https://biodsa.github.io/

[3] Wang, Z., Danek, B., Yang, Z., Chen, Z. & Sun, J. Making large language models reliable data science programming copilots for biomedical research. Nat. Biomed. Eng. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01587-2

[4] Wang, Z., Chen, Z., Yang, Z., Wang, X., Jin, Q., Peng, Y., Lu, Z. & Sun, J. DeepEvidence: Empowering Biomedical Discovery with Deep Knowledge Graph Research. arXiv:2601.11560 (2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.11560

[5] Wang, Z., Cao, L., Danek, B., Jin, Q., Lu, Z. & Sun, J. Accelerating clinical evidence synthesis with large language models. npj Digit. Med. 8, 509 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01840-7

[6] Wang, Z., Gao, J., Danek, B., Theodorou, B., Shaik, R., Thati, S., Won, S. & Sun, J. Compliance and factuality of large language models for clinical research document generation. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. ocaf174 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaf174

[7] Jin, Q., Wang, Z., Floudas, C. S., Chen, F., Gong, C., Bracken-Clarke, D., Xue, E., Yang, Y., Sun, J. & Lu, Z. Matching patients to clinical trials with large language models. Nat. Commun. 15, 9074 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53081-z

[8] AgentMD: clinical risk prediction using large-scale clinical calculator toolkits. Nat. Commun. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64430-x

[9] GeneAgent: self-verification agent for gene set analysis with database-backed verification. Nat. Methods (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02748-6

[10] Swanson, K., Wu, W., Bulaong, N. L., Pak, J. E. et al. The Virtual Lab of AI agents designs new SARS-CoV-2 nanobodies. Nature 646, 716–723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09442-9